Louis Vierne (1870-1937)

The Man and his Music

Reviewed by Eric Meece, a.k.a. Eric Mystic or E. Alan Meece

Mostly written in circa 2008-2009

The Man and his Music

The organ, yesterday and today

The Man and his Times

The Organ Music of Louis Vierne

The First Symphony

The Second Symphony

The Third Symphony

The Fourth Symphony

The Fifth Symphony

The Sixth Symphony

Pieces of Fantasie and 24 Pieces in Free Style

Orchestral, piano and other works

LINKS

Discography

The organ, yesterday and today

Louis Vierne of France was one of the great composers of the 20th Century. He wrote music for many instruments, but he is best remembered for his works for organ, which I will discuss below. However, this is precisely the reason why he is usually not recognized as a great composer; for just as the organ has been neglected in our time, so have composers of organ music. Today, especially in America, this majestic, mystical, so-called "king of instruments" is usually relegated to the church, which the majority of people do not attend regularly. Even there, the organ is usually only heard accompanying the choir or hymn singing by the congregation. Most people today are totally unaware that a wealth of good concert music exists specifically written for the organ that is not intended solely for church services. It is unfortunate that when many people today hear organ music they immediately think of the church which, with its formal rituals and oppressive or "superstitious" dogmas, may not be a pleasant association for them.

But such was not the case in other times and places. Earlier this century the organ, with its wealth of varying sounds and powerful sonorities, filled the role now performed by the symphony orchestra, which was not yet available in most American cities. Many concert halls and other public buildings which date from this time have magnificent organs built right in. Not only were original concert pieces performed on these organs, but so were transcriptions of many popular symphonic works. In Europe, the organ has had a long and illustrious history, with many fine composers and performers going back to J.S. Bach's time and before. In fact, many of the finest symphonic composers in Europe over the centuries were also organists and organ music composers, often beginning their careers in the organ loft. This includes the greatest German classical composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms, the Hungarian master Franz Liszt, plus many French romantic composers like Saint-Saens, Franck and Faure.

It was in France in fact, in the later 19th Century, that organs were first developed that could fill the role of today's symphony orchestra for the listening public. In Europe until then, as in America today, the organ was more commonly associated with the church. Organs and organ music in the time of the Enlightenment and the Revolution in the late 18th Century fell into neglect because of the skeptical and anti-clerical mood of the times. But in the middle of the 19th Century, new organs were built that were meant to appeal to the masses of people by emulating the new "symphonic" sound being developed by classical and romantic composers such as Beethoven. Even though most of them were built in great old French Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, these organs were as secular as they were sacred in inspiration (perhaps even blended the two).

The greatest of these organs were built by Aristide Cavaille-Coll (1811-1899). It is his organs you usually hear today in recordings of Vierne's music and that of other French romantic and modern organ composers. These instruments lack the ringing clarity of the earlier Baroque organs, created to bring out the various simultaneous melody lines in contrapuntal music such as Bach's. Instead, the sounds of the pipes in a Cavaille-Coll organ are meant to blend together harmonically in the way a symphony does, and their powerful reeds were created to stir the emotions like trumpets, trombones and cellos do in an orchestra. At left is a picture of the Cavaille-Coll organ at Notre Dame de Paris, where Vierne was organist from 1900-1937. Later on, the symphonic organ became the basis for other kinds of organs which appealed to the masses even more blatantly. These were the theatre organs which accompanied the silent movies, and the mighty Wurlitzers which toured the countryside in rousing concerts of popular music. Today, the largest church organs are usually built to combine the best qualities of Baroque or "classic" organs with those of the romantic or "symphonic" organs.

Cesar Franck (1822-1890) was the first composer to fully utilize the sound colors and other potentials of the new symphonic organs. His thoughtful, passionate works for solo organ are his finest works, and are usually ranked (perhaps along with Vierne's or Messiaen's) as second only to Bach's in the history of the instrument. Among these was a half hour-long work entitled " Piece Symphonique " (c.1862) which, without having specifically-numbered movements, sounds and unfolds like a symphony, with its romantic, orchestral-sounding themes, classical developments, recapitulations, and stirring concluding flourishes. This piece in turn inspired another French composer, Charles Marie Widor (1844-1937), to write over ten "organ symphonies" for solo organ in five or six movements each. The Fifth of these (1880) concluded with a "toccata" which, in some circles at least, is almost as famous and revered as Bach's "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor," and which substantially influenced the character of French and other organ music for decades. It was Louis Vierne, Widor's pupil and close associate, who brought this style of symphonic writing for the organ to its fullest and finest development. No doubt these French "organ symphonies" for solo organ also helped inspire Saint-Saens to compose his famous "organ symphony" for organ and orchestra in 1886.

Louis Vierne, the Man and his Times

Vierne in turn became known as a great teacher, as well as a composer and organist, whose students were the nucleus of the French organ school that still lives today. His pupils included Marcel Dupre, Joseph Bonnet, Nadia Boulanger, Olivier Messiaen, Maurice Durufle, Gaston Litaize and Jean Langlais. He taught at the Paris Conservatory as Widor's assistant in 1894-96; then became the colleague and assistant there of fellow composer Alexander Guilmant (1837-1911), whose organ sonatas also have symphonic dimensions and influenced Vierne's style almost as much as Widor's symphonies did. After 1911 he taught at the Schola Cantorum.

Louis Vierne was born on October 8, 1870 in Poitiers, France, in Vienne province (which interestingly has only one letter different from Vierne), about 200 miles southwest of Paris. I have heard rumors that he is related to famous science-fiction writer Jules Verne, and in fact his full name is Louis Victor Jules Vierne; but if so how did the extra letter get in his last name? Actually that name is probably related to the French name for Venus, which is quite appropriate since his music so reflects the spirit of this goddess of beauty. Organist David Sanger quotes from Vierne's writings, "I came into the world almost completely blind on account of which my parents felt a very keen chagrin. I was surrounded by a warm and continual tenderness which very early predisposed me to an almost unhealthy sensitivity. This was to follow me all my life, and was to become the cause of intense joys and inexpressible sufferings." In his youth an operation restored partial sight to him, allowing him to study and write music with the help of a magnifying glass. I am constantly amazed at how Vierne was able to play and compose so brilliantly in spite of this handicap.

The Vierne family moved to Paris, and then to Lille where Louis' Uncle Colin took him for the first time to hear an organ at the St. Etienne church. Later, back in Paris again, Uncle Colin brought him to the church of St. Clotidle where (at Colin's urgings) he first heard the music of Cesar Franck. Franck's music was a "revelation" that had a profound effect on his life, and helped to inspire his studies of the organ and piano. In 1889 Vierne became a devoted pupil of Franck's at the Paris Conservatoire, and was priviledged to hear Franck premiere in person his three organ "Chorals," the crowning glory of his career, on the piano (with the help of another pianist who played the pedal part). One year later this patriarch of French organ composers died of wounds from an accident on Paris streets. Meanwhile Vierne's father had also died, and the boy became head of the family at age 16. The untimely deaths of many of his family, teachers and friends became a constant and recurring source of sorrow for him.

After Franck died, Widor became Vierne's teacher and the leading French organist. A supremely cultured and articulate man, Widor also became known for his collaboration with the organist (and later famous humanitarian) Albert Schweitzer in producing new editions of Bach's works, including illuminating essays on how to perform each work. To this day they are the most widely used Bach editions among practicing organists. Vierne was such a brilliant student and devoted follower of Widor's symphonic organ techniques that he became known as "Widor Junior." He was Widor's assistant at the church of Saint-Sulpice by 1892, and accompanied him on a whirlwind tour of Germany for 3 weeks in 1898. In 1894 he won a First Prize for organ playing, but Widor encouraged him to become a composer and carry on his tradition of organ symphonies, aware that his brilliant young student had also internalized the essence of Franck's aesthetic genius as well as his own. Vierne married in 1898, and Widor played for the wedding at Saint-Sulpice. After their German tour Vierne and his wife went on a romantic honeymoon in Cayeux, and it was during these happy times that Vierne began work on his masterful and elegant First Organ Symphony and the great "Mass Solenelle."

According to Olivier Latry, the organist at Notre Dame who researched Vierne's life and recorded his works in the late 1980s, Vierne was "according to all who knew him....a particularly engaging person who was also extremely sensitive in spite of his rather cheeky appearance of a parisian street-boy." This character was reflected in Vierne's own sensitive and spirited musical works, which became darker and more austere in later years due to the many misfortunes that he suffered. In 1900, however, he gained the opportunity to become organist at the greatest and most famous church in France. His wife encouraged him to apply instead at a suburban church that would ensure greater peace and financial security, but after much confusion he took Widor's advice and became one of the 500 candidates for the post at Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. He was chosen unanimously by the review committee, doubtless not only because of his auditions and his resume as a top student and virtuoso performer, but because his standing as a brilliant composer had already been well assured by his First Symphony, completed the previous year. In those days, after all, an organist was expected not only to perform well but to be skilled in improvisation and composition, which is one reason why there have been so many great French organist-composers. He went on two years later to complete his brilliant Second Symphony, which reflected not only all that he had learned from his teachers, but also his own sensibility, conditioned as it was by the cultural ferment of Paris in his time; ground zero for the styles of impressionism and post-impressionism that were revolutionizing both art and music.

He carried out his post at Notre Dame with characteristic enthusiasm and dedication, and the organist became fused as one with his Cavaille-Coll instrument. Says Latry, his latter-day successor, "most of Vierne's organ works were inspired by the imposing edifice whose every secret he discovered as the years went by." His work helped to increase the prestige of the organ in general, and his organ loft became a cultural center and meeting place for many of the most influential artists and leaders of Paris in this remarkably creative period. Not only did the other great organist-composers of France visit there often, but so did such distinguished figures as Rimsky-Korsakov, Renoir, Rodin, Jaures and Clemenceau. You could almost say that in the 1900s Vierne was the French national organist at the French national cathedral, and indeed the music of this "very French" composer sometimes seems to embody the patriotic and revolutionary spirit of the times-- nowhere more so than in the finale to his First Organ Symphony, already his most famous and oft-performed work. Meanwhile he became with Guilmant one of the first organists to become a famous international concert performer.

The year 1906 brought a personal "earthquake" as devastating to Vierne as the great earthquake in San Francisco was to residents of that town. A series of disasters began that year which later led him to say that since 1906 his life had been one catastrophe after another. That year he suffered the same fate as his teacher Franck and was injured in a street accident in Paris, in which he injured his leg, threatening his career as an organist and destroying his health for months. He recovered, but his marriage was annulled by 1908, and his mother died the same year after a horrible illness. His son Jacques became ill simultaneously, and his friend Guilmant died soon afterward in 1911 from the same disease that killed his mother. Then he was ousted from his post at the conservatory, where he should have succeeded Guilmant as organ professor. Another great organist-composer, Eugene Gigout, was chosen instead, and meanwhile others plotted to take away his prized post at Notre Dame. The force of his personality enabled him to transcend all these problems and compose another organ symphony, his Third, that same year (1911), and soon afterward to begin work on his great series of smaller pieces (24 Pieces in Free Style), published in 1914.

That year Europe exploded in the First World War. Vierne fled to the west coast, where he composed his Fourth Symphony, whose style and mood reflects the catastrophe. By 1916, the year of the Battle of Verdun, the war had also become another personal catastrophe for Vierne himself, as his brother Rene (also an organist and composer) was killed in the war, along with many of his students. His son Jacques died in the war at about the same time, and the same year Louis got sick with glacoma, rendering him blind again. He had to take a four-year leave of absence to stay at a sanitarium, which cost him all his savings and property. Meanwhile his star pupil Marcel Dupre took over at Notre Dame. Felix Aprahamian says that on his first concert tour of America, Dupre was mistakenly billed as "the organist of Notre Dame" instead of as Vierne's substitute, an insult the sensitive Vierne felt deeply. On returning to Paris, he discovered that his Notre Dame organ had suffered war damage, and he set about raising funds to pay for a restoration by making concert tours, including trips to Ireland and Scotland in 1925 and the U.S.A. in 1927. Impressed by the organs he saw there, he also wanted (among other things) to add new combination stops and powerful trumpets like those found in some other Cavaille-Coll organs, but had to settle for a few new stops, a few repairs, and a more convenient pedal for the "swell" organ (the portion of the organ located behind shutters, which the pedal opens and closes for "swell" effects of volume). Even this was not completed until 1932, however.

Back in Paris in 1921, he composed a "Triumphant March to the Memory of Emperor Napoleon I," which I would say pretty well confirms what I said above about Vierne's patriotic sympathies. Two years later he wrote his massive Fifth Organ Symphony, and in 1926-27 he completed his wonderful set of 4 suites entitled "Pieces of Fantasie," planned as concert pieces for his huge American tour. His performance of these pieces is no doubt why he was such a hit there; David Sanger writes that he was recalled to the platform 10 times after his Chicago performance. Among these Pieces of Fantasie is his most famous work, "The Carillon of Westminster" (the theme music for my radio program from 1986 to 2010).

In 1930 Vierne went to southern France where he composed his Sixth Symphony and other works. His life was brightened now by, among other things, a new relationship! The same year three improvisations recorded in 1928 were released on 78 RPM records, along with the Andantino from the Pieces of Fantasie and works by Bach. He began a seventh symphony, but never finished it. In June 1937 he felt a strange feeling of sadness as he readied himself for a recital with his favorite pupil, Maurice Durufle. He played his Three Improvisations, and then Durufle followed for a while. Then he was given in braille a theme entitled "The soul redeemed from matter" to improvise on. After deciding which organ stops to use, he suddenly wavered, as a pedal note sounded from the organ. He placed his hand over his heart, then suddenly fell over and died of a massive stroke right there on the organ bench during the concert! It was a fitting if untimely and sensational death for a man who had already sacrificed so much, and who had dedicated his life to the instrument on which he died-- and to the enrichment of musical culture in his nation and his world.

The Organ Music of Louis Vierne

Here I make some reviews and comments on his music for the organ, concentrating on his symphonies and the Pieces of Fantasie.

The organ symphonies all have five movements, except the first which has six. Thus some people say these symphonies (like Widor's) should really be called suites. Like Widor's too, each succeeding symphony is written in a key one note up the scale from the last. They all begin in a minor key, but only the First, Fifth and Sixth have final movements in the triumphant major like a Beethoven symphony's finale would have. On the contrary, the Second and Fourth leave us in the deepest darkness and turmoil-- but energized and ready to tackle it head on! Vierne said that he was more interested in musical themes than tone color, and this is certainly reflected in the symphonies (though not in the Pieces of Fantasie).

In each symphony Vierne explores with ever-greater dedication the method of generating an entire symphony from a few main themes, the way a plant unfolds from a single germ; an ideal of symphonic writing exemplified by the most famous of all symphonies, Beethoven's Fifth. Perhaps no other composer in any medium pursued and realized this symphonic ideal as fully and consistently as Vierne did; even Beethoven rarely realized it outside his Fifth Symphony. This style is also called "cyclic," based on Franck's approach of continually returning to an original theme. Each symphony also takes us ever deeper into the chaotic and dissonant world of the 20th Century, without ever fully arriving there. His music is the oft-unacknowledged source for much of modern organ music, yet he always blended modernistic with traditional and romantic elements. His harmonies became more and more "astringent" as the years passed, straining tonality to the limit but never fully leaving it. Unlike today's "painters in sound" like Messiaen, structure remained very important to Vierne. He strides the boundary between the classic and modern worlds, which gives him a unique appeal and place in history. In his music we feel the uncertain sun rising over a new century and a new age; we contact the source of our own times with all their creative promise and constant perils.

His music contains the dramatic flourish and emotional pathos of romanticism, yet also has an impressionistic "pastel-like" quality that tends toward the dispassionate and abstract modernist styles. Like all Turn of the 20th Century composers, including his teachers Widor and Franck, he felt the strong, all-pervading influence of Wagner's spacious, dramatic chromaticism. In some of his later works we also feel a slight kinship to modern jazz and pop musicals. His chromatic melodies and sometimes "jazzy" chords almost seem precursors to Gershwin. Remember, he was there-- Paris in the twenties-- epicenter of the "jazz age." In his brighter works Vierne seems to be giving us a glimpse of this vibrant world and reminding us that life is a carnival. If he were to be classified, however, I would call him a post-impressionist. Especially in the Pieces of Fantasie and his smaller works, but also in his symphonic scherzos and some other movements, we hear the impressionistic side of Vierne, reminding us of the elegant, wistful and wispy French style of Debussy and Faure. On the other hand, like the post-impressionist painters such as Cezanne, his works always have structure, strength and "backbone;" and we always have the sense, however strange his chromatic wanderings may seem at times, that his music is going somewhere. His closest kinship may be to Ravel, just 5 years his junior; although his work has a deeper and more solemn sensibility than Ravel's.

The First Symphony in D Minor, Opus 14 (1898-99), is said to have "caused something of a stir," and remains in many ways his best and most popular. It was dedicated to his friend Alexander Guilmant. Unlike some authorities (maybe including even Vierne), I especially appreciate this one because, among his symphonies for organ, it is the one most like the kind of symphonies I know best by composers like Beethoven. If they were to write a symphony for organ, this might be what it sounds like. And this doesn't detract from its originality. Unlike the music of symphony composers, though, it begins with a Prelude and Fugue in the style of Bach; the only one for organ he ever wrote. Though ambitious and well-crafted, the fugue doesn't quite measure up to the best ones by the great Baroque master (but then, whose do?). The first movement however is quite satisfying; solemn, spacious and dramatic; apparently much influenced by Franck. Like all of his movements, it is developed with great care and consistency from a simple theme. Its first three notes also become a cornerstone for the finale's main theme later on (in the portion where the theme switches briefly into b minor), and a following four-note descending figure is similar to the finale's second theme. It builds toward an intense climax and a dramatic pause; followed by gradual release. The Fugue is built on the D Minor tone followed by a four-note arpeggio figure ascending from the diminished seventh. It carries this theme through skillfully, but the movement seems a bit forced and strained compared to the great fugues of the Baroque era.

The third and fourth movements are some of Vierne's most sensitive ever. The lyrical Pastorale has a hauntingly sweet middle section between an engaging oboe melody. This main tune contains an early hint of Vierne's "cyclic" theme writing, since the second theme of the Finale is very similar to it. The scherzo (called Allegro Vivace) is a model of symphonic writing comparable to the best orchestral scherzos. It also has a beautiful, lyrical middle section that haunts our imagination, a trio tune played on a trompette stop in canon with the pedals. Then we move into a quiet and tender Andante that may seem boring to some listeners, but gains appeal the more often we listen. Like the quiet section before the finale of Beethoven's Fifth, it seems as if we are being held in suspense before being thrust into a magnificent adventure; and indeed we are. Again the theme is almost the same as the Pastorale, and the same theme re-appears again soon afterward, slightly modified, as the second theme of the noble and heroic finale.

What words could I write about this magnificent masterpiece that would do it justice? Other commentators have said things about this Final like "one of Vierne's most celebrated pieces...a movement one never gets tired of hearing" (Nicholas Bray), and a piece of "splendour and magnificence" (Hans Fagius). David Sanger correctly describes this "one of Vierne's most famous movements" as beginning in "bustling broken chords in the manual parts" over a "joyous pedal melody." This technique of placing the melody in the lower notes, accompanied by fast-moving broken chords in the higher notes, reverses the normal procedure of accompanying a melody in the treble with chords in the base. Wagner seems to have pioneered it in such famous pieces as the Ride of the Valkyries and the Tannhauser Overture, and Widor made it a prevalent feature of French organ music through the Toccata from his Fifth Symphony. Vierne's first finale is a wild, ecstatic ride comparable to Wagner's gigantic German amazons gliding down the Rhine. It is the epitome of "travelling" music. When I first heard this Final I felt like I was flying in a jet airplane, crossing rapidly over vast scenery while making daring turns as the two melodies of the movement modulate, develop and intertwine with each other. Since then I have decided that the "bustling" pairs of broken chords over the main pedal melody are exactly like a horse galloping, and perhaps this is literally what Vierne meant to convey. If so, I can think of no better comparison than to Jacques Louis David's famous picture of the conquering Napoleon riding on horseback across the Alps. Here we see Vierne's apparent "patriotic" sympathy for the progressive and turbulent tides of modern French culture and history. In fact, the first several notes of the pedal melody itself are almost exactly the same as the first notes of the French national anthem melody, La Marseillaise. (with historic pictures). He is speaking through music the aspirations of the French, and of all of us. (In fact, about 12 years after I wrote this, Vierne biographer Rollin Smith confirmed that in fact Vierne did refer to his First Symphony Final as "my Marseillaise.")

After a passage that seems closely related to a portion of the first theme of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony finale (another piece probably inspired by La Marseillaise), the theme sounds again in full pomp and splendour in the manuals, this time in counterpoint with a second theme in the pedals. Then the music quiets down and we hear the second theme again in canon form, this time more tenderly and completely rendered on the oboe and string stops. Next, portions of the two themes combine for some brilliant snatches of scenic sound; but the volume is still intensely subdued, as if we are being propelled through some distant, secret and wonderful visionary realms. As we approach the return of the main theme again, the sound builds suspensefully. This time the broken chords magically transform into triplets instead of pairs over the pedal theme, and then we move into a climactic final section that combines everything we have heard. Perhaps this change from pairs to triplets represents a shift into higher gear; we have emerged from our 6 minute adventure ready to cross boldly into a new land, now aboard a train, an automobile or a motorcyle instead of the old-fashioned horse, but still moved by the same heroic vision. Indeed, composed in the progressive era of the Dreyfus Affair, when enthusiasm for the French Revolution was reviving and innovation exploding, it seems as if this piece is launching us all into the hopeful new world of the 20th Century where the aspirations of the 19th would be realized. The Final of the First Symphony appeals to us first and foremost as a powerful masterpiece of compact writing, in which few if any notes are wasted. But many listeners are probably unaware of this movement's deeper dimension as the picture of our dramatic human journey together across the pages of history, from the great Revolution to our still-unrealized destiny of freedom in one world. This uplifting music gives us the strength and hope to successfully meet our personal and collective adventures, spiritual as well as secular, as no other music does. In the innocent and hopeful times of 1899, however, neither Vierne nor anyone else yet suspected what terrors and trials both he and all of us would have to endure before we arrived at the promised land.

The first version I heard of the Vierne First Final was that played by Pierre Labric in 1984 at my college library, right after which I was inspired to begin writing a toccata of my own at the nearby Unitarian Church in San Jose. But I also felt sure there were better versions around, and the E. Power Biggs version I also heard that day didn't satisfy (too staccato), but soon I found others like the LP version by Hans Fagius, and the Chorzempa CD version above (on the same organ that Labric played). But Labric's lively performance was what first evoked for me the music's ecstatic and scenic flights. More versions are listed here and in the LINKS below.

Diane Bish plays the First Finale and

here also introduces it

18 year-old Kevin Neel plays the First Finale on You Tube

Mark Cyphus plays it

La Marseillaise on organ

We certainly got some prophetic hints of the trials to come in his Second Symphony in E Minor, Op. 20, written in 1902 well before they began to unfold. Although I have a special affection for the First because of its magnificent finale, the Second Symphony is probably his best overall. In the First Symphony there are only hints of reappearing themes, but the Second clearly unfolds from the germs of the first movement's main ideas. Yet this unfolding is rendered so subtlely that most listeners don't notice. Together with the First Symphony's finale, in the Second's first three movements we hear the peak of his symphonic writing. Certain pieces of Vierne, like the greatest of Bach's organ works, make us feel transported into heaven, and the finale of the First and the Allegro and Choral of the Second are among these. In the Allegro, with its dark and turbulent mood, it seems like we are storming the gates. This dynamic Allegro is as thoughtful and powerful as the best symphonic Allegro movements, reminding me of the first movements of Beethoven's Ninth and Brahms' Fourth. It unfolds spaciously and logically toward an intense climax. The following Choral is obviously modelled on those of Franck. Like Franck's, Vierne's chorale theme is original, not based on a hymn tune; built out of the two main themes of the first movement placed in reverse order. The lyrical second theme of the Allegro is heard with some rhythmic pauses added, followed by two softer reworkings of the Allegro's sharp opening bars. This Choral is certainly one of the most melodic, grand and enjoyable pieces Vierne ever wrote, and reminds one of Ravel's Bolero in the way it builds toward a climax. The dramatic ascension to the chorale theme's ecstatic re-appearance at the end is certainly one of the longest and most eloquent you are ever likely to hear. The dancelike Scherzo is yet another masterpiece, revealing Vierne in his most typical impressionistic mode. This third movement employs the technique of the First Symphony's finale, as the Allegro's theme is modified and presented hauntingly subdued in the pedals under the radiantly delightful and sparklingly liquid phrases in the high notes. In this movement we feel vividly the inviting but transient nature of Vierne's younger days in Paris, and perhaps we envision the lost days of our own youth as well. One You Tube listener wrote "Just love that pedal theme that seems to glide through water."

Although some commentators have said that the first two symphonies are totally classic-romantic in form, to me it seems that in the last two movements of the Second we are already entering 20th Century territory. In the wonderful Cantabile the main Allegro theme is rendered in a languid and sometimes meandering way that is soothing to the soul. The Final clearly picks up where the Allegro left off, with its main theme reappearing only slightly altered. At first hearing this movement may seem so chaotic that it's as if all the notes of the Allegro were jumbled up in a blender and thrown back out on the page again. Far from the triumphant Beethovenian apotheosis, in the Second Final we are left feeling even more aroused and frustrated (but not yet defeated) than when we started in the first movement! Brilliant and unique as it is, this Final is a demanding movement for the listener; not the crowd pleaser that the First Symphony's finale is. Perhaps if this movement had been easier to follow, the Second Symphony might have achieved the wider popularity that it deserves. But those who can discern all the masterful, clever and intricate ramblings amidst the melodramatic chords will be rewarded for their trouble.

Organist Jean-Baptiste Dupont plays the 2nd Symphony Final

The Third Symphony in F# Minor, shortest of the six, was written in 1911. It may seem a little short on musical brilliance and emotional satisfaction compared to the Second, but is still a masterpiece of symphonic writing. The Allegro Maestoso may seem less than majestic to some listeners, with its sharp and jagged edges. But its solid and imposing chord structures are majestic enough. So is the rush of descending chords near the end. Once again the opening bars generate much of the momentum for the whole symphony, but not as overtly as in the later symphonies. The attractive Cantilene is a bright spot in this work, with some mellow, inspiring passages. In the scherzo-like Intermezzo, the rhythmic outlines of the opening theme can be discerned, although the notes are different. It is very listenable and refreshing in a quiet way. The Adagio, the symphony's longest movement, is a noble and tender melody with manifold musical transmutations that takes us on a journey through Vierne's emotional uncertainties. In the Final the original jagged theme is smoothed out into a graceful melody, still in the minor key, that conveys an emotional tone of wonder and hope but not yet of happiness. This movement is clearly modelled on the popular finale of the First Symphony, almost as if it were a sequel or reworked version of it. The themes are beautiful, and it uses many of the same techniques and moves through many of the same phases as the earlier work; but the result is somewhat less compelling than the original. Pedal notes provide innovative harmonies, though. Then toward the end, a powerful new element is added; an intensified rendering of the theme in slower time. Then the feeling of triumphant apotheosis returns, as the key shifts to the major and the symphony ends on a cheerful and positive note. Though not as great as the First finale, it still stands as a masterpiece of symphonic form and classic beauty in its own right.

young master Gert van Hoef plays the 3rd Finale well

Or hear Third Symphony Finale on You Tube

Peter Bengtson plays the fifth and last movement of Louis Vierne's Third Symphony

A single haunting, sustained note repeated four times opens the Fourth Symphony in G Minor, Op. 32, setting a dire tone reflecting the Great War that erupted in the era it was composed, as well as sorrow over the loss of people in his life. Just as the First Symphony embodied the hopes of its time, so now the Fourth injects us into the sobering world of 1914. Four pairs of chromatic notes, two ascending and two descending, serve as the austere and unmelodic theme for the slow opening Prelude and the entire work. Mr. Houlihan points out that this theme includes all the notes in the chromatic scale. Though we might expect this dangling, unresolved theme to take us nowhere, the Prelude unfolds with relentless logic and consistency. Soon the quiet trompette stop hesitatingly sounds a more reassuring theme, a truncated version of the original, but it fails to halt the main theme's apparent march to doom. The following Allegro is built on this short trumpet theme, and is one of his finest and most compact allegro movements. Despite some chromatic wanderings, it is easy to follow and satisfying to hear. It is actually a bit less intense than the stormy Allegro of the Second Symphony, giving us the sense of serious activity but no longer of doom. Soon a fugue passage is built from the theme, and in other quiet passages it is heard backwards. Then the austere first theme returns as the foundation for dramatic "arch-like phrases" (as David Sanger calls them) which bring the movement to an astounding close.

In the following Minuet Vierne takes us back to the romantic times of the glorious Summer before the Guns of August; a welcome relief that reminds us what we have just lost amid the horrors of war. The elaborate dancelike theme seems to bear no relationship to the austere opening bars of the symphony. In the enchanting middle section, however, the original sustained note sounds in the background, and a portion of the trompette theme reappears, as if to remind us that we haven't really escaped from reality. Still, we are allowed for a while longer to continue our escape through one of Vierne' most sublime melodies, the Romance; but not without the (somewhat artificial) intrusion of the dire original theme. In the Final we are taken right to the front lines of battle to become witnesses to the great catastrophe. Its intensity is comparable to the Mars movement of Holst's The Planets, also written in 1914. The original Prelude theme is here transformed into a rapid perpetual motion machine developed with high mastery. At the end we come full circle, as the original theme becomes a series of slow chords, followed by four repeating tonic chords that return us to the beginning-- but this time in the triumphant major key (a prophecy of French victory?). All in all this much neglected work, though downcast, is one of Vierne's most enjoyable and accessible; well-crafted, spacious, majestic and melodic. It clearly stands as one of the finest of the French organ symphonies.

Daniel Roth plays Vierne 4th Finale at Brooklyn

Hear the Fourth Finale on You Tube played by Christopher Houlihan

In the last two symphonies Vierne enters the modern post-Great War world of increasing dissonance and atonality. For those who like modern music, these symphonies are more challenging and stimulating than the earlier ones. The Fifth Symphony in A Minor, Opus 47, was written in 1923-24. It is the longest of the six symphonies, but to my romantically-inclined ear it is the least satisfying; though full of riches for the dedicated and sophisticated listener. Composed right after the series of great catastrophes in Vierne's life and the life of Europe, it feels as if Vierne is here trying to build a new order out of the ruins of post-war chaos and destruction. But just as such a new order failed to emerge from the 1920s in Europe, so Vierne's new musical order falls a bit short of its goal in the Fifth Symphony.

Sweeping away all the extraneous romantic rubble from the past, Vierne builds his massive edifice from the foundation of two themes, one a series of descending diatonic tones, and the second an ascending and descending chromatic theme similar to the Fourth Symphony's main theme. Both are heard alternating together within the first few bars of the opening Grave movement. Unlike in previous symphonies, Vierne restricts much of the music to developments of these two themes alone; an unprecedented attempt at economical composing. In the way these themes are constantly brought back in new ways, it is more masterful in its "cyclic" technique than earlier symphonies, where sometimes (as in the Romance of the Fourth), a theme sometimes returns seemingly out of context. The Grave movement is similar to the Prelude of the Fourth Symphony; in fact throughout the Fifth we hear echoes not only of the preceeding Fourth Symphony, but of the following Sixth as well; it's sometimes hard for me to remember which movement is from which symphony. But whereas the Prelude of the Fourth is dire and frightening, the Fifth's "grave" prelude has a brooding, melancholy mood that reflects post-war dissillusionment, and which Sigfried Schibli says "is reminiscent of Wagner's Tristan." Another of Vierne's fine allegro movements follows (called Allegretto molto marcato), in which the main diatonic theme is inverted and accompanied by the chromatic second theme. Though very similar to the Fourth's Allegro, it contains rather more dissonant wanderings than its predecessor, making it a bit less accessible to most listeners.

The third movement is the most successful; Schibli even calls it the pivot of the whole work. The two themes are brought out sharply and clearly. Without being given any particular program, musically this Scherzo is a magnificent example of what I call the "bewitched" style, as the melancholy mood becomes a spooky one. In its rhythms and melodic passages there are clear similarities to the famous "Sorceror's Apprentice," written by his colleague and contemporary Paul Dukas. The Larghetto, though too long and not especially striking or memorable, has some beautifully expressive moments woven from the chromatic second theme and the inverted first theme. In the Final the opening theme is heard again in the pedals, sounding out strongly and triumphantly in the major key, accompanied by a ringing carillon in the manuals. We seem entered upon another magnificent adventure like in the First finale; only to be diverted by the chromatic second theme, this time with its two ascending and descending phrases placed in reverse order. The following elaborate developments not only don't seem "economical," but are out of place in a movement that opens in such a bouyant and joyous fashion. The chromatic second theme seems too irresolute and mysterious by nature to balance the bold diatonic first theme here; although it might have worked had Vierne put it in the major key, and if the movement had been shortened. In the last 3 minutes, however, the resolute structure returns and, except for some needless dissonant notes, the promised joyride is given to us after all. We are transported through ecstatic scenes reminiscent of the First Symphony's finale, and the theme itself is transformed at the end into one last dramatic statement. With the worst of his catastrophes behind him, Vierne now returned in his symphonic writing to the hopeful mood of his First for the first time since it was written, as he looked forward to his successful final years.

Hear the Fifth Finale at Saint Sulpice, Paris

In the supremely virtuoso Sixth Symphony in B Minor (Op. 59, 1930), I believe he achieved something of the new order that he didn't quite reach in the Fifth. As Siegfried Schibli said, by now he didn't have to "slavishly" adhere to the principles of cyclic form to demonstrate them effectively, and the result is a more "relaxed" and less rigid work. In the opening Introduction and Allegro we hear his finest allegro movement since the Second Symphony. It is said that he ventured to the very limits of tonality in this movement, but the dramatic lines are strong and easy to follow anyway. After a brilliant and elaborate first theme, a mysterious chromatic second theme appears that complements it nicely. Then some searingly dramatic passages appear over a pedal point (sustained pedal note). Later the first theme is transformed into imposing rapid chord sequences that anticipate the finale, and in turn seemed to have been anticipated by some passages in the previous movement-- the finale of the Fifth Symphony, that is!

In the following Aria we are given a few glimpses of the bright Victorian pre-war world that also re-appears in some of his Pieces of Fantasie written a few years before, although the dominant mood here remains mysterious and detached. Another of Vierne's brilliant Scherzo movements follows, almost identical in conception to the one of the Fifth Symphony. The first movement's main theme is brought out clearly, and later rendered upside down. It is another " bewitched" movement that Schibli says "has an iridescent quality that sometimes stops little short of the grotesque." The Adagio opens hauntingly and broodingly over a pedal point, then leads us wandering through intriguing chromatic labyrinths that probably leave most listeners bored or baffled. Fortunately the Final, though full of astringent harmonies, is much more comprehensible. Here the second theme of the first movement is transformed into a rousing statement of pomp, splendour and show-biz razzumatazz that "sweeps all before it." Next to the First, it is the most enjoyable and popular of his symphonic finales; truly a tour-de-force, and a fitting and optimistic conclusion to his daunting symphonic journey. After the rousing opening theme, another elaborate, attractive, carnival-like theme is heard quietly in the pedals, with sprightly accompaniment in the manuals; but it doesn't seem to take us anywhere yet. But then the opening finale theme abruptly reappears and leads us into brilliant, exciting passages in which portions of it are combined not only with the second theme, but with the opening allegro's theme too. Spectacular scales up and down the pedals lead us toward the symphony's dazzling conclusion in loud, chromatic "jazzy" chords similar to those that ended the first movement.

Sixth Symphony Finale

The Sixth Finale, preceeded by a portion of the Adagio

The Pieces of Fantasie, Op. 51 and 53-55, written in 1926-27, contain many of Vierne's best organ works, and many of my favorites. The 24 pieces are grouped into four suites of six movements, and each suite is longer (and more magnificent) than the last. Unlike the symphonies, the movements of these suites have little or no internal connections between them, and thus are correctly named. Nevertheless all the suites could be considered symphonies in the sense that they all have scherzos, slow movements and magnificent finales; about all they lack are the symphonies' turbulent and intensely-serious allegro movements. They are not meant to be serious, after all; they are enchanting impressions with picturesque titles that explore various realms of feeling and imagination. Some of them are named after a colorful kind of musical form, but most are images; an interesting ironic achievement for a composer who himself could barely see. I will briefly comment on most of the pieces from the four suites.

The first suite is the least interesting of the four, and if you don't like it you should not be discouraged from listening to the other three. The Prelude is a fitting intro to the entire series. It is the most archetypical Louis Vierne piece; with its pastel, carnival-like melody in the pedals over sprightly manual phrases, it is similar to the Second Symphony's scherzo. The famous Andantino was the one recorded on 78 records; it is pleasant and typically Viernian in its harmonic ingenuity, but not strikingly moving. The Requiem Aeternam is noble, sensitive and brooding. The concluding March Nuptiale is the last thing I would want my organist to play at MY wedding; it is too brash and lacking in grace. Also heard in the middle of the first suite are a Caprice and a scherzo-like Intermezzo.

Hear Vierne play the Andantino

The second suite begins with an interesting and brooding Lamento and an attractive Sicilienne, but it is noteable for its last four movements, beginning with the Hymne au Soleil (Hymn to the Sun). It is a bit strained, but at times reveals the full magnificence of His Stellar Majesty's solar radiance. This suite also contains a contrasting Clair de lune (moonlight), a long-winded but beautifully-melodic piece worthy of Debussy. Also included is a magnificent example of Vierne's foray into what I call the "bewitched genre," Feux Follets, which I believe translates into either "jack o' lanterns" or "will-of-the-wisp." This Halloween-like scherzo, unlike the scherzos in the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, is aptly-named this time, leaving no doubt about Vierne's intentions to explore the spooky and paranormal within these "fantastic" musical realms. Foolish ghostly sprites appear to dance mischievously across the ethereal upper reaches of the keyboard, as if evading the organist's attempts to catch them. The second suite concludes with a brilliant Toccata, which takes its place alongside the other great French toccatas by Widor, Gigout, Boellman and others. It's dynamic ascending and descending phrases rush by so quickly that it takes many listenings to fully appreciate them.

The third suite opens with a heart-felt but meandering Dedicace, and continues with the Impromptu, among the most often-performed and typically Viernian of the Pieces of Fantasie; noteable for its pastel-like impressionistic qualities and graceful, craftsmanlike poise and balance. The Etoile du soir or "evening star" is quietly, serenely and eerily beautiful. Then comes another, even more characteristic " bewitched " piece, Fantomes (phantoms), which is darker and scarier than the jack'o'lanterns and "will o' the wisp" from the previous suite. Amidst the netherworld of the hereafter, various departed spirits debate the future destiny of humanity. From this murky and spooky realm we emerge immediately into the magnificent, smoothly-flowing vistas of the Rhine River in Sur le Rhin, one of Vierne's grandest and most majestic compositions. But an even grander concluding piece follows: Vierne's most famous work, The Carillon of Westminster. The ubiquitous clock-tune of Westminster Abbey, heard every hour on-the-hour in cities and towns all over the planet, is here gradually transformed into a magnificent, transcendent celebration of time and eternity itself. Much like the Choral of the Second Symphony (with which it bears the closest similarity among the symphonic movements), it gradually builds in intensity toward its awesome and heaven-storming climax. In this grand essay we feel connected to the various civic and sacred monuments in our own towns and cities, much like the Big Ben Towers of London, which give our lives meaning amidst the day-to-day grind and provide assurance of God's presence in our lives here on the Earth. It is often played for New Year's Eve services, helping us to reconcile ourselves with the passage of time and to take note of its significant landmarks and milestones.This piece was my theme music to open my radio program Mystic Music for 24 years, chiming the noon hour, and was used to mark the passage to the new year on the station's Visionary Music Marathons.

The concluding fourth suite opens with another typical Vierne tune, the Aubade or suitor's morning serenade to his lover from outside her window. After a moving Resignation, the following piece, Cathedrales, dazzles us with the heights of Vierne's spiritual inspiration. Perhaps the most attractively-impressionist of the Pieces is next, the Naiades or "water spirits." Then we arrive back outside the cathedral again, but this time gazing upon its barbaric and scary darker side, the Gargoyles and Chimeras, in another "bewitched" piece.

The concluding finale is yet another great carillon piece, Les Cloches de Hinckley (or The Bells of Hinckley.) More unique, unusual and original than The Carillon of Westminster, it is no less grand and eloquent. With it we come full circle to the finale of the First Symphony, with its pair of broken chords over a joyous pedal tune. This time, however, with this more meandering, mystical theme, we celebrate not so much the triumph of human freedom and progress as the spiritual salvation of the soul. Next, an ostinato figure in the manuals rings out the bells' peaceful strains while the pedals meander in fascinating, hauntingly-inspired phrases. Listening to these opening minutes of this magnificent piece, one feels connected to and at peace with the spiritual life of the Earth, much as the people of Europe do whenever they hear the huge, beautiful bells ring out across their ancient landscape from atop their many magnificent cathedrals and churches. Then, as the theme transfers to the manuals, the listener follows Vierne through some atmospheric chromatic phrases, which build gradually in aspiring beauty and intensity to another of his inimitable grand climaxes. Here the original pedal tune and manual figure returns with a quicker and sharper rhythm. According to Thierry59 on the organ music forums on Magle's website, organist Pierre Labric wrote that "Vierne stayed in Hinckley when he toured in England, Ireland and Scotland in 1925. He gave a concert on the 5th of may 1925 at the Parish church of St Mary on a beautiful instrument built by Norman and Beard in 1908. As Vierne and his "amoureuse" Madeleine Richepin spent the night in an hotel in front of the church, he was waken up every 15 minutes by a chime ringing a descending scale in E major. On the morning, Madeleine Richepin suggested to Louis Vierne to use the distressing theme of the chime for a composition. This idea was very soon taken up by Vierne who wrote effortless in the train to Tenbury this piece of fantaisie. From the Pierre Labric's recordings in Saint Ouen de Rouen." On the Magle site, acc confirms that Rollin Smith (who recorded the great version of Widor's 10th Symphony Finale and wrote a biography of Vierne), reported that the chimes at St. Mary's sounded every 15 minutes. The St. Mary's Parish website about the Bell (site no longer available) said that it was actually the chimes ringing every 3 hours that awakened the light-sleeper Louis Vierne, and that he stayed with his distant relative who was the organist there. On their organ site we are also told that an organist died while at the bench there on Good Friday 1932. Of course, 5 years later Vierne suffered the same fate at Notre Dame.

Among other organ works is another series called the 24 Pieces in Free Style, Op. 31 (1914). All except two have one-word titles that represent free musical forms. They were composed as pieces that could be used at the offertory during services. If you are a practicing organist, you are more likely to be able to learn these than the larger works. They show Vierne's skill as a miniaturist, for each piece is a little world unto itself and represents a uniquely personal mood. Most reveal Vierne's marvellous harmonic ingenuity, and many are among his most hauntingly sensitive and beautiful. These pieces are:

Book One

24 Pieces in Free Style, Book I 1-12, performed by Serge Ollive

1. Preambulum, by Stephen Ketterer

2. Cortege, by Diane Drury (dramatic)

3. Complainte, by Georges Bessonnet

4. Epitaph, by Stephen Ketterer; grand and moving in a quiet way

5. Prelude, by Francis Jackson: pleasant and carnival-like in Vierne's typical manner; a good intro to the set

6. Canon, by Georges Bessonnet (imitation piece, like the canons in Bach's Toccata in F)

7. Meditation (pensive), by Massimo Gabba

8. Idylle Melancolique, by MrTenoregrande (beautiful)

9. Madrigal, by Daniel Cook (pleasant, tuneful)

10. Reverie, by Daniel Cook; a favorite of mine among these

11. Divertissement, by Pastór de Lasala; a brilliant, lively piece with strong rhythm

12. Canzona, by Daniel Cook

Book Two

24 Pieces in Free Style, Book II 13-24, performed by Ben Oosten

13. Legende, by Olivier Latry, titular organist at Notre Dame (my favorite; nostalgic and haunting)

14. Scherzetto, by Ed Bruenjes

15. Arabesque, by Stephen Ketterer (long, slow, mysterious and elaborate)

16. Choral, by Ben Stein

17. Lied, by Matthew Mainster (one of the best of the 24; "Lied" means song, and it has a lovely tune)

18. Marche Funebre, by Georges Bessonnet (long; good tune, but drags a bit as you might expect)

19. Berceuse (lullaby), by Jared Post; perhaps the most popular

20. Pastorale, by Edward Taylor; one of my favorites to play

21. Carillon (de Longpont), by Kare S. Eddinger

22. Elegie, by Daniel Cook (lovely)

23. Epithalame, by Georges Bessonnet; subtle and a bit hard to get into

24. Postlude, by Georges Bessonnet; has flourishes, but too complicated and seems somewhat disorganized

Legende and Madrigal, arranged for Horn Quartet

Berceuse and Epitaph, arranged for Horn Quartet

Among his other organ works are two great Masses, called Messe Basse, one written in 1912 and one in 1934. Christine Kamp has given us expert renderings of these works on the St. Ouen organ in her CD releases (festivo records). These works both contain a prelude, introit, offertoire, elevation, communion, and a final movement. Here is the 1912 work performed by Serge Ollive. More well-known is his beautiful earlier work for organ and chorus based on the Latin Mass, the Messe Solennelle. The grand Maestoso is a version for solo organ of the opening Kyrie movement. Here is Messe Solennelle on You Tube from Notre Dame de Paris.

The Triptyque from 1929-31 includes a Communion. Another earlier piece called " Communion ", Op.8, is one of my favorite Vierne pieces to play. It was probably written in 1894. It presages much of what he wrote later, and reminds me of scenes and art from Paris in the 1890s and 1900s. Below is a recording of me playing Communion.

His first work Allegretto Op.1 was published in 1894 by Charles Marie Widor in a collection or works by young organists called L'Orgue moderne. Maurice Durufle also transcribed Three Improvisations which Vierne recorded in 1928, which includes the March Episcopal.

Vierne also wrote one interesting Symphony in A Minor. It came between his second and third organ symphonies, and is traditional and romantic in style. Emotionally it reflects the series of catastrophes in his life that were beginning at that time, especially the collapse of his marriage, better than the Third Organ Symphony of 1911 does. It was well received by critics and public. Its orchestration is powerful, but rather spare. The first three movements are downcast, while the finale is uplifting. The themes of the movements are related, as in the organ symphonies, but not in a rigid way. I find the third scherzo movement to be the most compelling. Vierne found writing a symphonic score to be a major strain on his very limited eyesight, and so unfortunately he never tried the form again.

For his 1927 American tour Vierne put together a Piece Symphonique for organ and orchestra, and played organ. 3 movements were chosen: Scherzo from Symphony 2, Adagio from Symphony 3 and Final from Symphony 1. The piece is performed on CD by Christine Kamp and the Holland Symfonia Orchestra, Ermanno Florio Director, in the Haarlem Philharmonie. The hall is home to an 1875 Cavaillé-Coll organ. As of 2021 it's available from OHS :

https://ohscatalog.org/louis-vierne-volume-4-christine-kamp-and-orchestra/

Other works include many fine solo works for piano, duets for piano and violin, many other wonderful chamber works, a poem for piano and orchestra, and his sensitive and passionate vocal music often based on French impressionist poems. I will add more information here on these works later.

Piano works

These are brilliant and often more accessible since they are generally less modern and adventurous in their melodies and harmonies, and may remind listeners of other composers.

Prelude #1, Prologue from 12 Preludes Op.36 excellent (or is it Op.38?) Performed by Georges Delvallée

Prelude #3

Prelude #6

3 Nocturnes Op.34 Performed by Georges Delvallée

Hear Vierne's Aubude for piano, Olivier Gardon plays

I highly recommend Vierne's chamber works, which have been collected in a double CD on the Timpani label. More information on this CD can be found on the Vierne discography page (click on link below).

Two pieces for viola and piano (1895)

Quintet for Piano, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, Op. 42, I. Poco lento--Moderato, by Danish String Quartet

II. Larghetto sostenuto

III. Maestoso Agitato

Click here for a lengthy (but incomplete) discography of Vierne's works, including those mentioned here, plus his works for other instruments

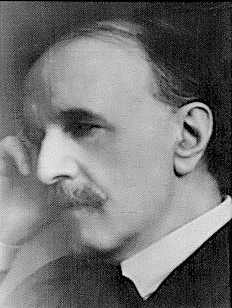

First photo of Louis Vierne from Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; copied from liner notes in Composers in Person (EMI classics)

Second photo of Vierne in melancholy reflection from Symphony in A Minor (Timpani records)

Third photo of Vierne at the organ console from Olivier Latry, Pieces of Fantasie (BNL).

4th picture of elderly, smiling Vierne with cigarette from primephonic (see links).

Large photo from google images or wikimedia commons.

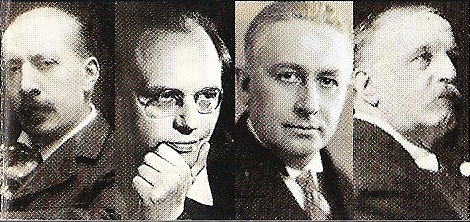

I believe the photo below of Vierne and his three colleagues is from Composers in Person.

An excellent catalogue and source of recordings by Vierne and other organ music is available from the Organ Historical Society at P.O.Box 26811, Richmond VA 23261 USA

Web site: ohscatalog.org

This is the website for the society itself

Phone: 804-353-9226, Fax 804-353-9266.

E-mail: catalog@organsociety.org

Any other questions or comments? E-mail me here or at my yahoo address

We are lucky that some new commentary and information has become available on the net and you tube since I wrote this essay at the request of the classical.net editor back in circa 2008 (with some small editing, new links and additions in 2021, and before). Some recordings from earlier years are no longer available, but others come along all the time.

Classical Net Home Page

Back to top of Louis Vierne page

Discography

Live lecture on Vierne with Christopher Houlihan

Interview with Olivier Latry Oct 6, 2020, about Notre Dame organ and celebrating Vierne's 150th birthday

A Death at the Organ: The Life and Works of Louis Vierne video

Interview with Rollin Smith on Vierne by Christopher Houlihan

The Epic Death of Louis Vierne

Wikipedia article on Vierne and see the French version here which can be translated (more or less)

Answers.com

Louis Vierne works from CD Universe

Primephonic listening site on Vierne, with reviews free trial and then a fee

Also check Amazon.com and use their search box.

A plea on You Tube for Organs, for Organ Music, Love and Life in our hearts and a warning against rampant, profitable real-estate development

La Marseillaise, arr. by Berlioz with pictures of French history

Organ music forum on Magle's website

Vierne "himself, knew the Final of the First Symphony, which he called "my Marseillaise," and the Carillon de Westminster had popular appeal."-- Rollin Smith

Carillon of Westminster

left to right: Widor, Messiaen, Dupre, Vierne

Fly Away with my essay about some other Marseillaise-like music by Beethoven and The Who.

Also related to these essays is Reverberations in Place and Time

Bach's Toccata in F for organ is an image of the kundalini! Bach, Chakras and Tarot; an esoteric, metaphysical adventure with lots of You Tube recording links

Virgil Fox performs Bach's Toccata in F in concert

Bach's Toccata in F on YOU TUBE illustrates the meaning of Tarot trumps

My list of favorite organ pieces with many links to You Tube, etc. to hear them

My organ compositions, sometimes inspired by Vierne

Eric Meece Homepage

Horoscope for the New Millennium