TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITIONS

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

A. Statement of Purpose

B. Plan of the Paper

A. Existentialism

B. Essentialism

C. Summary of the Debate

D. Contrast to Materialism

E. The Opposition is Fundamental

F. Clarification of Terms

SECTION TWO: COMPARISON OF PLATO AND BERGSON

A. Plato on the Changing

B. Plato on the Forms

C. Bergson on the Forms

D. Bergson on the Changing

E. Summary of the Debate on Metaphysics

A. Plato on Reason and Opinion

B. Bergson on Intuition and Reason

C. Can Plato's Reason Also Be Entitled "Intuition?"

D. Different Visions of the One

E. The Absolute

F. Comparing Plato and Bergson on Intuition, Reason and Opinion

A. The Priority of Soul over Matter

B. Two Kinds of Order

C. Recognizing the Two Views of Spirit

D. Plato on the Soul

E. Bergson on the Soul; Comparison to Plato's View

F. Plato's View of Matter

G. Bergson's View of Matter

H. Things in Space

I. The Receptacle: Space

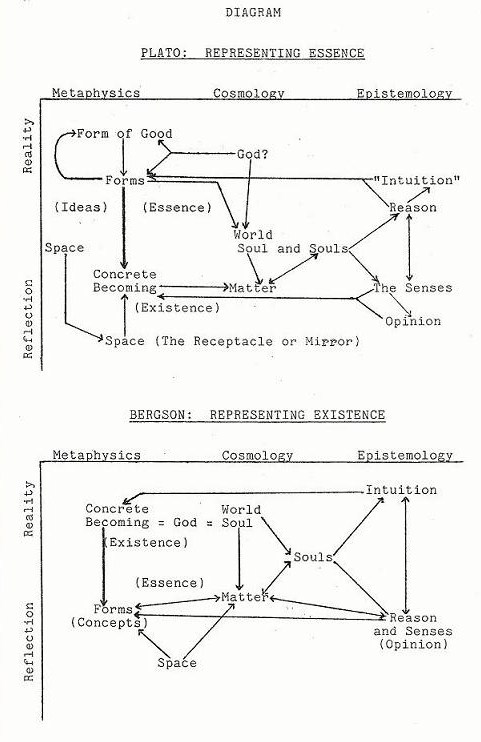

J. Diagram and Explanation

SECTION THREE: RESOLVING THE QUESTION ITSELF: DO FORMS EXIST?

OR: which is prior: essence, or existence?

PART ONE: EVALUATING THE DEBATE

A. Argument Against Bergson

B. Argument Against Plato

C. Are Forms Real?

D. A Dialectical Method

E. An Empirical Method

A. Forms as Human Utensils and the Human Body

B. Forms of the Soul

C. Forms As Creativity

D. Forms as Colors and Sounds

E. Forms as Weights

F. Forms as Geometrical Forms

G. Forms as Mathematical Laws of Nature

H. The Form of the Good

I. Summary of Which Forms Exist

PART THREE: CONCLUSION: THE OPPOSITES RECONCILED

A. Forms as Numbers

B. Forms as Time

C. Conclusion

BIBLIOGRAPHY

diploma

LINKS

SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITION

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

Are there such things as essences? If so, are they the original source of things, or are they merely the intellect's thin abstractions from the lived concrete reality? This is the question to which most philosophical searches return. It is the great argument in philosophy between those who believe existence is prior to essence and those who believe the opposite. It could be stated as the interest by a philosopher that something is, as opposed to what something is. In other words, proponents of existence are interested in exploring the concrete, living, fluid existence of everyday reality, while proponents of essences are interested in exploring the general nature of various phenomena, beyond its appearance in particular concrete examples. To reason, or just to be; that seems to be the question.

A. Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to examine the case for each side and determine the merits of each, at least on some issues. As philosophical "lawyers" and advocates I have called on the venerable Plato to represent the proponents of essences, and the great modern philosopher Henri Bergson to represent the proponents of existence. It being generally recognized that Plato is the chief proponent of the view that the phenomenal, changing, visible world is the image and shadow of the eternal, unchanging essences or forms, and this being nothing else but essentialism; and since existentialism is the opposite view, I propose to compare Plato's philosophy, as illustrating essentialism, to that of an existentialist philosopher. If Plato represents essentialism, and existentialism is the opposite, then the opposite view should be best represented by the opposite to Plato's view, which would propose that the phenomenal, changing, visible world is the original, while the unchanging and eternal forms are the shadows and images. This I take to be the view of Henri Bergson, generally recognized as the chief proponent of the view that the changing, concrete reality, which he called duration, is the original of which the forms are the faint shadows and images in our intellect; this view here defined as existentialism.

I shall present the two philosophers as opposites, best representing the two philosophies, essentialism and existentialism, which will shortly be thoroughly defined. This is not the only way in which Plato and Bergson could be represented, but by so representing them, I hope to clarify the question whether the forms are the shadows in our minds of the concrete reality, which we do best to pay better attention to, or whether the forms hold the key to understanding that concrete reality. The goal is to try to reconcile the two sides. But this cannot be done if one side is buried in the other as its mere reflection, so we can pretend it does not exist. The opposition must first be presented clearly and forcefully.

It will be my contention that Plato and Bergson are archetypes of this great debate, especially in their two major works, Plato's Republic and Bergson's Creative Evolution. Nevertheless, the main purpose of the paper is not to show that Plato and Bergson are archetypes of the argument between essentialists and existentialists, but to use them as examples and support in outlining the argument itself and its possible resolution.

B. Plan of the Paper

In pursuing this aim, I have organized the paper into three sections. In the first section I define each side of the debate, and in the process say how each side argues against the other and attempts to criticize and debunk their assertions. In the second section, Plato and Bergson are presented as examples of each position. In the third section I will again evaluate and investigate the question of the debate itself, and this time I will attempt to at least begin to see where the truth lies among the conflicting points of view.

The first section includes this introduction and statement of purpose, followed by the definition of each philosophy and the terms existentialism and essentialism. In my definitions, I will also outline the main lines of the argument itself as I frequently see and hear it presented in readings and in discussions, as well as in my own mind. I will show the way each side handles not only those issues to be dealt with in this paper, but also some other issues that will not be dealt with. This will give the reader an over-all, comprehensive picture of the scope of the debate, and show why the proponents of each side believe it so important to take the position they do, and what motivates them in doing so. I will also clarify why I have used the terms I have used, such as "existence" and "existentialism," instead of others that are possible.

In the section comparing Plato and Bergson, I will zero in on three closely related areas of disagreement upon which all the others depend. The most basic of these three questions will be covered first. It is the fundamental question we must ask, and what the debate is all about: what is real, and what is the reflection? Do forms exist, and are they the essences of which concrete, changing things are imperfect and fleeting images, examples, copies, reflections and shadows? Or is concrete existence real instead, and the forms merely concepts and categories that represent imperfectly the fluid reality that forever escapes them? I will show how Plato and Bergson represent perfectly the contending sides of this question, and in presenting their arguments I will have effectively presented both sides of the debate.

This is what I call the metaphysical question. But there is another aspect of the debate so closely related to it that I cannot omit discussing it altogether without omitting important arguments which each side needs. This is the epistemological question, or the question of which is the best way of approaching reality: reason or intuition. It is clear that the answer to the question of how we know reality is tied to the question of what reality is. In discussing what is real, we cannot really omit discussing how it is that we ourselves contact that reality, and which faculty it is that gets us in touch with it. In fact, both Plato and Bergson frequently use epistemological terms to describe the metaphysical reality; as for example when Plato describes the two realms as "the visible" and "the intellectual," or as "the realm of knowledge" and "the realm of opinion." I have simply separated this aspect of what is really a single question from the metaphysical for purposes of clarity and organization. 1

Then there is a third aspect that we cannot ignore if we are to do justice to each side. For each philosopher claims his approach not only upholds essence on the one hand and concrete existence on the other, but that by doing so he exalts spirit over matter. Each claims as the prime motive for his ideas the liberation of the soul from the pollutions of the material world, with its necessary and mechanical movements. Each claims that matter has not the indubitable reality the materialist claims for it, but instead is a fall from true being and dependent on it. No comparison of two opposing philosophers can ignore their main thesis, especially when it is one they happen to agree on!

How is it that Bergson and Plato are so diametrically opposed and yet agree on their central thesis? It is clear we must clarify where they agree and where they differ. We must clarify how each philosopher relates the debate over form versus existence to that over spirit versus matter, and show how in arguing for form on the one hand and existential becoming on the other, each is therefore arguing for the spirit. Indeed each philosopher and his followers claims that the exponents of the other side in the existence versus essence debate are really materialists, and see little or no difference between their two opponents. It is though each philosopher were fighting a two-front war; that they see their two opponents as close allies who, unknown to themselves, are practically indistinguishable from one another. For Bergson, matter and mathematics are so close that one is the mere extrapolation of the other. For Plato, matter and the changing, concrete world are just about the same. In reality, however, the debate is not over spirit and matter, or mind and body, but over essence and existence, whether each side realizes it or not. We must not confuse one debate with the other. Thereby Plato and Bergson do not get accused of being something they are not-- materialists-- which to them is like being called in error.

In a sense, what I am doing is extending the epistemological aspect of the question to include how each side believes our whole soul relates to metaphysical reality, instead of just one of its faculties, that of knowledge. This latter faculty gets called different names depending on which we regard as real, essence or existence; while for our purposes the terms "soul" and "spirit" are equivalent. The question also becomes which philosophy is really the spiritual one, which can bring us salvation from the pollution and degradation of the material world. Later I also call this topic "cosmology," or how in each philosophy God or the world's soul or spirit creates the world.

After I have established the opposition between Plato and Bergson, as well as the conflict between the two philosophies in general, and in the process have shown where the two sides agree, I will follow with the third and final section. There I will evaluate the central thesis of the two sides, showing there is some validity and some inadequacy in each. The main part of the third section will be the examination of forms themselves to see if they really exist. That forms exist will be found difficult to prove, yet evidence will be offered to show that they are at least possible. What will emerge clearly, however, is that if they exist, we can only prove them to do so by seeking their manifestation within the realm of concrete becoming itself. It will also be found, provisionally at least, that the true view of reality lies somewhere between the diametrically-opposed views of Plato and Bergson; and that in some ways formal essence and concrete, changing existence interpenetrate. My thesis will be that both of these philosophies are true, and that each deserves to be taken seriously. Therefore both are wrong in seeing the other's point of view as wrong, and lost in mere reflections of reality. The truth is that neither essences nor existence is true alone; that essences, if they exist, are to be found within the realm of concrete becoming, or existence, and that existence contains these forms within it. I do not say that both philosophers are really saying the same thing, because they are not. They are die-hard opposites. What I say is that the truth lies in the attempt to reconcile them.

PART TWO: DEFINITIONS

Let us define the two philosophies which Plato and Bergson exemplify.

First let us define existentialism. It is a movement embracing many different views and philosophers, include many who disclaim the label. But it is all based on a central idea; that existence is prior to essence. Existence is the concrete reality of being as it is immediately encountered, while essence is the general nature or set of traits that characterize what exists. Those who believe existence is prior to essence say that life cannot be enclosed in any category, because it is too fluid and interpenetrating. It must always elude the concepts, formulas, and definitions that are meant to confine it within a definite nature that limits and determines what it is and what it can do.2 Those whom I shall call existentialists believe our primary attention should be on existence in the concrete and flowing. Rather than define or conceive what you (or things) are, existentialists are interested in the bare but mysterious fact that you (or things) are.3 The closer one remains to the concrete, flowing, living reality, they say, the richer your experience, and the greater your energy, because you are in closer contact with, and thus have access to, yourself and your faculties. But you have more philosophical knowledge too, because you are in contact with reality in its fullness rather than its component parts, which are isolated for purposes of definition. These components are the static and unchanging concepts and categories of the intellect into which we group the fluid reality of being. But these concepts, forms, and essences are actually only remnants of reality, not reality itself. The existentialist says that dependence on them lessens consciousness, because they cause reality to appear ever and always the same as before, just as you had calculated beforehand in your mind.

For existentialists, there is no difference between Plato's idea of forms and our usual idea of "concepts" or "categories." At root, they are both the same, and the word "forms" has no other meaning. These concepts, such as "justice" or "beauty" or "two" or "bed," etc., are only the exterior bounds of reality. They are the shell rather than the contents; the shadow rather than the substance. In addition, these concepts and thin, pre-formed categories are only symbols, labels and models of reality, not reality itself.4 This means intellectual, conceptual knowledge is relative, too, because it stands outside the object, and thereby takes a particular and incomplete view towards it. However many names, symbols, or concepts we use to describe an object, says the existentialist, we can never duplicate the simple and complete act of experiencing the object itself.5 The existentialist believes these empty, fragmentary concepts of the intellect, mistaken by essentialists as the essences and eternal forms of things, threaten to take us away from the rich, fluid reality of life and lock us up into our own heads. Existentialism considers the intellectual approach opposite to its own to be aimed toward manipulation and control for the purposes of security and safety, rather than for true knowledge, because these aims require predictability, in which you already know how life will turn out. It aims, in Bergson's words, to make us "masters of matter."6 But life is not like this, it is insisted, because the situation one is trying to enclose in utilizable concepts is always changing and escapes the intellectual net. It recommends, instead of intellectual calculation, openness to change and willingness to take risks. In knowing, this means "intuition," a less well-defined but more immediate way of knowing in which, through feeling and sympathy, one resonates and communes with the object itself and becomes aware of its aliveness, without trying to define and categorize it. This way one knows, for example, that all life is interrelated and always fluid, or what it is that a living person really needs and wants in their innermost being. It means the ability to know facts through feelings and psychic abilities that a logical investigation might have found by a much more lengthy and tedious process. It means contact with the fluid reality which can then lead to better interpretations in science.7

This point of view has vital implications extending beyond the questions of what exists and how we know it, which are the questions this paper deals with. In conduct and personal affairs, for example, it means to maximize freedom and voluntary action instead of action that is the result of a prior plan. This is the only alternative, say existentialists, to following the predictable result of the intellect's planning, which imitates, and thereby succumbs to, the predictable mechanical movement of the very material processes which it seeks to master. Here we see the contemporary protest of humanity to remain human and not become a machine. Insecurity and personal responsibility are stressed, and it is denied that a human being is something in particular, or has an essence or character (beyond our history and current condition); we can and must make ourselves whatever we choose to be.8 Not only freedom, action, and responsibility, but heightened consciousness is an existentialist goal, and this heightening comes through greater and greater movement and willingness to change, so that one is open and not closed to experience and growth.

B. Essentialism

Those who believe essences to be the primary reality I shall call essentialists. Their case runs as follows.

Their opponents who state that concepts are only the thin contractions of fluid reality imply there are no distinctions to be discerned in our experience. They thereby reduce reality to an amorphous, unitary mass of which nothing can be identified, characterized, or talked about, leaving us in chaos and confusion.9 The essentialist grants that nothing can be separated exactly from anything else in the phenomenal world, and that categories may rigidify reality. And yet, they ask, who can deny that there are distinctions in our experience? If the world is not as sharply-defined as the concepts we use to describe it, that does not mean they are not valid at all. Cats may not be all that different from dogs, yet most animals of those two kinds do fall rather nicely under those two categories.

What is it that accounts for the evident distinctions and different qualities in our experience? The essentialist believes it is the essences of things, or the "forms." This means he believes the real essence of the things we see are not the particular examples, which are too fluid and changeable, but the form or first principle, known by reason, which is the general idea which includes and explains all such examples, and which is known only by the intellect.10 According to him, the fluidity of the world does not measure up to the clarity and precision of the forms. But if essentialists believe in precision, they say it is their opponents who overdo it. For existentialists demand that general concepts fit exactly the experience they represent, or they dismiss them. On the other hand, it takes sensitivity to see the generalities around which the fluid world clusters.

It is foolish, therefore, to seek truth and reality by simply paying attention to the immediate, concrete flow of being. One is not able that way to discern the categories and essences around which reality gathers, such as cat, or red, or justice, beauty and goodness. Nor can one discern mathematical structures in the world that way. For nature, including human nature, is not simply a fluid continuity; there is an order, which must be discerned by reason.11 How can we know this order, the essentialist asks, without the formulas, symbols, categories, and definitions that allow us to chart its structure and to see it clearly? How can you know mathematical theorems, or Newton's laws, or Einstein's equations, by paying attention to the flow of reality, and ignoring its form and structure?

Consciousness is hardly lessened by reason, as existentialists claim, when without it we are hardly conscious in any normal sense. For we require the concepts of the mind to make any sense of the world and to see more than a chaotic and confused hodgepodge. And it is the existential view which is relative and superficial, because it merely pays attention to immediate reality and does not seek out its relation to what is not immediately known. Through thinking we are able, by making logical leaps and connections, to understand and imagine other possibilities which can later be verified.12 Existentialism is relative because it deals with the unique and contingent, which may be true today and here, but false tommorrow and elsewhere.13 For existential objects are always changing and particular, while essences are necessary, universal and eternal. The latter one can know; the former only opine about.14

The placing of essence prior to existence leads to a drastically different stand on the question of conduct and personal affairs. What about freedom and action? They are empty goals, in the way existentialists pursue them. The essentialist says we cannot act freely without the planning that the so-called already-known, pre-formed concepts enable us to do. According to Glenn Morrow, a Platonic scholar, thought helps us to understand and master our situation, and only thus can we be free.15 It is a measure of our freedom that we have been able to master matter and nature, as well as to comprehend the cosmos; these, and not attention to our own subjective and personal "vital flow." If we are merely open and attentive, and do not think, we jettison important tools. Adventure, taking risks, action for action's sake are denounced by essentialists as blind action.16 Unless we grasp out certain elements and have a clear picture of alternatives readily useable, we will not make the right choices. It is folly to dispense with all knowledge known beforehand, especially when we need the guidance of tradition, which the existentialist so fears.17

Making knowledge into "feeling and sympathy" is also highly dangerous, says the proponent of essences. Feelings are unreliable, and can lead us astray by arousing us to satisfy and tittilate them, regardless of what reason tells us is the right thing to do. We must control our feelings by reason, which can give us an objective view free from our own wants and desires. Only through reason can we know a system of unchanging principles and values which guide one toward the wisdom and morality that is beyond compromise to the changing needs and impulses of the existential situation. This is true moral responsibility; the genuine kind of "freedom" jeopardized by the so-called liberating existentialist destruction of rational standards.

Eternal essences are the key to an invisible order, or "intelligible world," underlying the apparent chaos; an order that gives purpose and sure direction leading beyond the existential abyss. So freedom and responsibility are claimed on the essentialist side, too, along with purpose. And essentialists say theirs is also the way to a higher consciousness. For it can transcend mere analysis, which breaks down experience into pieces, to reach a vision of how everything participates in a universal order. This might be found through the great systems of philosophy, whether it be Plato's theory of forms, Leibniz' monadology, the Great Chain of Being, or Hegel's dialectic. Or it could be the rational coherence necessary to put together a theoretical study of any subject at all.

Let us, then, summarize the terms of this epic debate of essence versus existence, between vitality and intellect.

The existentialist insists that existence, or the concrete reality of the immediately lived, is the primary reality and proper object of philosophy. The essentialist insists instead that the primary reality and object of philosophy is essence, or the world of ideas, concepts and general laws of the mind.

The existentialist believes the changing flow of becoming is more real than the static and unchanging forms extracted from it. The essentialist believes eternal and unchanging forms are more real than the changing and perishing world which is their reflection.

The existentialist promotes intuition, or contact and communion with the inward life of the object, as the best method of approaching reality. The essentialist promotes reason, or knowledge of the general concept or structure which explains the object, as the best method of approaching reality.

The existentialist believes categories and concepts are superficial and relative; the essentialist says immediate perceptions are superficial and relative. The existentialist believes the intellect only rearranges what is already known; the essentialist believes it can help us discover unknown realms through speculative imagination.

Existentialists eschew prediction and planning as deadening to freedom and creativity; essentialists say you are not free or creative unless you can plan and predict. Existentialists believe risk and openness to changing reality is the competent way to live; essentialists believe this existential way is merely acting blindly.

The existentialist believes feelings are closer to reality than reason, which is only their outward shell. The essentialist believes the feelings and passions are unreliable and subjective and distort knowledge by urging us to confuse reality with the way we want things to be. Existentialists believe the door to reality is through attention to the vital flow of the self; essentialists say that knowing one's own consciousness is only a partial and uncertain view of the truth.

An excellent summation of the problem, admittedly from an existentialist view, is provided by Rollo May in his book Existence. We can do no better than to quote it:

I could have used an essentialist spokesman (such as Morrow) for this summary. But it would make no difference, for the essence of the conflict would remain the same, and May has captured it beautifully here. Essentialists want to know the general nature which all apples share; existentialists want to contemplate the individual apple itself, and insists especially that the concrete individual human being not be forgotten in any picture of reality.

D. Contrast to Materialism

Yet in spite of all this disagreement, my acquaintance with each side of the argument convinces me they have at least one point in common: they both put themselves on the side of spirit as against matter. In other words, both philosophies are spiritualist and anti-materialist, and we will see that this is true of both Plato and Bergson. I should define what these two philosophies are. Materialism states that matter, the inert, lifeless stuff of the universe, is not only real but the primary basis of things into which everything resolves, and that its necessary and lawful movement, rather than an invisible vital force, is the cause of all actions. Spiritualism, on the contrary, states that the spirit or soul is primary; that consciousness, however defined, and however indefineable and invisible, underlies whatever lifeless, unconscious stuff there may be in the universe, and is the source, at least for humankind, of its movement and action.

As examples of this spiritualism on both sides of the current discussion, we need only cite Sartre's Existentialism as Humanism and Bergson's Creative Evolution19 on the existentialist side, and Plato's Phaedrus 245, Timaeus 34 and 46 and Laws 896, and Leibniz's Monadology on the essentialist side. When Plato in the Phaedrus speaks of the "soul" as having its source of movement within, he differs little with Sartre's declaration in Existentialism as Humanism that "a human being is not a stone," but has subjective life through which he makes himself and "propells himself toward a future."20 Heidegger can also be considered a spiritualist because he analyzes all of being in terms of its human mode, or Dasein, and characterizes it as "care" or "its own disclosure to itself."21 These are modes of consciousness,22 and yet he uses them in describing not only human beings, but being or reality itself.

The really fascinating thing about this agreement on this one issue is that if one resolves, as I have, that spiritualism is to be preferred, then one has two alternatives still confronting you. Your position has not been resolved after all; your philosophy not determined, for you still have to decide which version of spiritualism to adopt. The battleground has shifted, as it were, to higher ground. Spirit could be reason, the eternal harmony of forms; or it could be will, action, and the flowing movement of sheer existence. Each side tends to see the other as closer to materialism than its own position is.

Existentialists are regarded by their opponents are still too close to the material world because they adhere too closely to the immediately existing. They resemble sense empiricists (who are generally materialistic) who refuse to consider what cannot be immediately seen. Since spirit lies beyond the visible, concrete world in an invisible, abstract mode of being, to seek the spirit in the concrete is to miss the spirit. Furthermore, the existential emphasis on the contingent and the mortal is dangerously close to leaving one in Plato's world of the perishing, and it is only material objects that perish. Many people, essentialists or not, notice that this obsession and over-emphasis on the mortal, human world closes off many existentialists to many spiritual realities and possible realities, such as reincarnation or a divine direction to the universe. Existentialists counter that the contingent, the changing, or the flowing are just where spirit is, because spirit cannot be pinned down by the static and fixed abstractions of the mind. To be contingent is to be uncertain and unnecessary, which perhaps means unknowable and even perishable, but also means indeterminate and free. And freedom (or as Plato says, self-moving) is an essential characteristic of spirit, a characteristic jeopardized by the essentialist emphasis on order, law, and design in the universe, and by their pre-formed concepts into which reality must be fit in a pre-determined and predictable way. The abstract concepts of our minds, says the existentialist, are what is closer to matter, since ideas are fixed, unmoving, rigid, necessary and external to one another like material objects are.

I believe that there are probably two true philosophies, and one false one. The false one is materialism, while the true ones are essentialism and existentialism, which each cover half the truth. There may be some truth in materialism too, but in this paper I am agreeing with Plato and Bergson that there is little truth in that view. Indeed, in the third section it will often occur that to question or disprove the existence of forms will be to show they are merely an aspect of matter and necessity, which for both philosophers and philosophies would be to prove them to be reflection, as mentioned above. It is a contention that Bergson asserts and Plato strenuously denies. Bear in mind that when I say Plato and Bergson are not materialists, I do not mean to say they are idealists, in the sense that they deny the existence of the external world. They only say that matter as atomists and evolutionists describe it is not the first cause of all things, as materialists assert; that matter is an appearance or deficit of which spirit is the reality.

The agreement of Plato and Bergson (and many of their colleagues on each side) on the priority of spirit is probably the common ground of the opposition between them. It is an ancient wisdom and observable reality that opposites always have something in common. For example, hot and cold have temperature in common, while up and down have direction. Plato and Bergson have a spiritual approach to understanding reality and its reflection in common. One is the near-exact counterpart of the other. They may or may not be perfectly opposite, but by highlighting their opposition I bring out the opposition of form and becoming more clearly.

E. The Opposition is Fundamental

This opposition I believe to be fundamental, far beyond a restricted problem or question raised by two philosophers. It offers a key to what is real. That this is true is shown by the fact that in one form or another, the debate over essence and existence has dominated Western philosophy down through the ages. We can see it in the conflict of Parmenides and Heracleitus, and even in Plato and Aristotle; although Aristotle was also an essentialist. We see it in the debate of realism versus nominalism, and it surfaces again as the debate of rationalism and empiricism. Even in the arts it appears as the constant tension between classic and romantic.

More evidence that this opposition is fundamental is provided by modern physics. The principle of Indeterminacy, developed by Heisenberg and others, is the basic law of quantum theory. It states that the position and motion of a particle cannot be measured at the same time aaccurately. The opposition of "position" and "motion" is roughly the same as that of form and becoming; especially since "position" also means the ability to observe and know any atomic particle. Bergson at least identifies forms as "successive positions," as we will see. What is most amazing about this principle is that the opposing terms are linked to each other in an exact relationship that remains constant. Bohr called this "the principle of complementarity." Here is independent evidence that the opposition of essence and existence is not only fundamental, but that each of its terms depends on the other and is its reflection and counterpart.23

Whenever an opposition appears to be stubborn and constantly persisting, we have reason to suspect that the two sides are necessary to each other to their own existence. We realize they are two, and yet really one.24 This is a basic principle of Eastern thought; it is the same contention that I am making here in saying that both forms and concrete becoming are true and are found each in the other. Reality acts as its own reflection.

F. Clarification of Terms

One may ask why I have chosen the term "existentialism" to represent the view that the lived world, whose characteristics are that it is concrete and flowing, is more real than the essences of the intellect. I use it because the chief trait of the lived world is that we confront it existentially, in the concrete experience of everyday life. I use it instead of "experiential," "empirical," or "phenomenal" because such terms denote a passive, a posteriori attitude, or even a materialistic one. While empiricism is similar to existentialism, the two are not identical (although Plato would not hesitate to call "the changing world" "empirical"). For existentialists believe that the concrete, flowing world is primary and fundamental; thus, a priori. And existentialism is not a passive philosophy, but an active one. Most of all, receptivity to external ideas outside the self is sggested by the terms "experience" and "empirical," whereas "existential" means the totality of the lived world in which the self, which is active, creative, and self-subsisting, and its experiences are included.

Similarly, the term "essentialism" may be thought confusing, because Plato defines the essences as what "really exists." The term essentialism, however, simply means that essences are what is held to be fundamental reality and a priori.

Existentialism includes not only belief in the priority of "bare existence," described with such words as "concrete," "immediate," and "lived," but also includes the ideas of "becoming," "movement," "flowing," and "fluid." Proponents of existence believe in the central importance of time, the basis of change and opposite of "eternal." In other words, Plato's "changing and perishing world" is their fundamental reality. The "existential" is "the temporal" and is the opposite of Plato's "essential" or "eternal." Heidegger, for example, went so far as to entitle his masterwork Being and Time, and in it he declared that "being is temporality" and that Dasein "always finds itself in history."25

Actually, existentialism is not so much declaring the positive fact that "being is becoming," but more that concepts and essences, themslves fixed and unmoving, do not describe it, whether these concepts be "being" or "becoming" or whatever. To say that existentialists believe "being flows," means they believe it escapes the conceptual net. Plato's description of "the changing" is no different, for he says it never exhibits a form constantly and consistently. Only Plato, unlike the existentialists, says this means the changing is a shadow of the real.

In using the term "existentialism," I do not wish to suggest that the philosophical position it refers to is limited to those philosophers commonly thought of as existentialists; still less to those who entitle themselves such. I could have used another term; however, since it seems to me that the placing of concrete, flowing existence prior to essences is exactly what recognized existentialists as well as others not labelled as such maintain, I might as well use the term. Why use another term since there is already a term in existence for what I am in fact speaking about, and that most people who read philosophy understand?26

Finally, since this paper deals with the conflict of two definitions of "reality," I should clarify what I mean by "reality" in case there is any question. There is doubt, for example, whether this is a proper word to use in translations of Plato.

When I, in this paper, say something is real, I mean that it exists. But I also mean that it is genuine. In other words, something is more real that is just what it seems to be, and is not confused with an image or copy of it. Any image, whether in a mirror or in our minds, is real, since it exists. But if we mistake the image for the original, then it is clear we are not in touch with reality, but are deluded. When, in this paper, I ask what is real, therefore, I am only asking which is the original, and which the image. I believe both Bergson AND Plato speak of being or reality in these terms.

Back to Top of Reflections on Reality and its Reflection (almost)

COMPARISON OF PLATO AND BERGSON

And now to further analyze the debate over essence and existence I call upon the two chief advocates for each position in the philosophical debate. Plato will represent essentialism, and Bergson will stand for existentialism. I trust that the appropriateness of these choices will be demonstrated by how well what they advocate corresponds to the definitions given above, and how remarkably and completely they are opposed to each other at least on the basic issues. I can find no better contrast between essence and existence.

PART ONE: METAPHYSICAL

The metaphysical question is the most basic issue of the debate, and the issue upon which all the others turn. This is the question of what is fundamentally real. On this question Plato and Bergson take opposite stands. Plato believes the forms are more real than becoming, while Bergson believes becoming is more real than the forms.

Let us begin by describing Plato's view of becoming, or "the changing."27 First, he says it evades all attempts to categorize it under the forms and concepts of knowledge, such as beauty, justice, light and heavy, and so on. The changing can appear one way, and appear as the opposite at the same time or from another point of view. In other words, the changing is changeable because it can never be described the same way twice. In this sense, it is not fundamental reality. It is never entirely heavy, just, or beautiful.

In Book Five of the Republic, Plato explains this basic characteristic of "the changing" (or "becoming")

Second, Plato says the changing becomes and perishes. It is not immortal, but is subject to birth and death. It does not stay the same forever, but comes into being and then perishes. An example of Plato's statement on this appears in Book Seven of the Republic, where he speaks of the study of arithmetic and geometry by the future guardians of the state. There he describes the changing world as "the perishing world" and contrasts the study of it to the study of "the real world."29

Third, the changing is visible. It is known through the senses, especially sight. Our senses reveal the qualities of hard and soft, colors and sights and sounds; trees, animals and bodies. Since the same object may appear in many ways as part of the changing world, none of these qualities are always given to the senses in a clear and distinct way, but often in a confused way. When they appear to us confused, reflection is able to sort out the true categories of being, such as hard and soft, one and many.30 Sometimes this visible world is called "the world of appearance."

Fourthly, the changing is multiform. The senses reveal many hard and soft things, but never hard and soft as the one essence. Many just actions, good people, and beautiful things are seen, but the real qualities of justice, goodness, or beauty as unified beings are not to be found in the changing world, which only exhibits a collection of particulars.31

Fifth, and most important: the changing is less real than real existence. It is something less than being, and more than non-being. His notion of Becoming is related to that of time, which in the Timaeus is described as "the moving image of eternity." (Timaeus 37D)32 The changing is considered to be the image and reflection of real existence. In the myth of the cave, Book Seven, he uses the terms "images," "copies," and "shadows" to describe the changing world of many things. For example, he says that the philosopher who returns to the cave "will recognize what each image is, and what is its original, because you will have seen the realities of which beautiful and just and good things are copies."33

We will now briefly indicate what, in contrast to the changing, is Plato's view of what "really exists."

In a word, what really exists are the "Forms" or "Ideas." The Forms or Ideas are the essences or real natures of which the concrete things of appearance are the imperfect reflections and images. These essences are known by reason. Forms are permanent and unchanging, and are furthermore unique and singular. Thus, the form of bed, beauty, justice, or hardness never changes, nor can it be confused with another form. We see these traits of the forms explained in Book Six of the Republic:

This theory of forms is explained further in Book Five:

Here in this passage we see that all forms are separate, even those opposite to each other. Forms are identical with themselves, and only appear to be many things through the agency of action and physical things, which are part of what he means by "the changing."

At the end of Book Five, we find the clearest statement in the Republic that forms are eternal and unchanging. There he says that "those who contemplate things as they are in themselves, and as they exist ever permanent and immutable" can be spoken of "as knowing, not opining."36 This means they are dealing with what really exists; in other words, with the forms, which are eternal and unchanging. 37

Admittedly, the Republic does not contain the clearest of all statements of Plato's theory of forms. This is to be found in the Symposium, in the speech of Diotina, dealing with the form of Beauty:

Let us summarize Plato's position on form and becoming. The forms are real; becoming consists only of mere shadows, copies, and images of the forms. The forms are single, unique, separate, and distinct from one another, and are known only to reason. They are static and unchanging, and appear in the visible realm as confused and vague facsimiles. In this visible mixture of becoming are found many things, which may resemble one or another of the single, eternal forms, and are called after them, but which are not forms, because no visible (and bodily) thing can copy forms exactly. Instead, such visible and changing things are constantly exhibiting many different and conflicting forms; yet never fully exhibiting any of them.

There is a genuine moral and spiritual message to be drawn from Plato's philosophy. It is that our desire for beauty and longing for truth can never be satisfied by the perishable things or the tempting goals of the ever-changing bodily realm; that only something lasting and essential, which we need only rediscover, can satisfy our true needs.

But there are other messages to learn, and other ways of expressing the same message, and if Henri Bergson is right, he not only has such a way, but builds it from an opposite view to Plato's, whose philosophy may in many ways actually take us away from what is true and genuine.

Bergson does not disagree substantially with Plato's description of the nature of forms and the changing. Here we may discern only disagreements in detail. What he disagrees about is WHICH IS REAL, AND WHICH IS THE REFLECTION.

He states his position in no uncertain terms:

In other words, forms are not independent realities, of which changing things are copies, but are mere extractions, "copies" if you will, from the movement of change itself. Yet to posit the forms as real existence, becoming must be reduced to a mere shadow of the forms, a "diminution" containing no more than the forms themselves. And is this not what Plato declared in the Republic when he placed becoming in the interspace between being and non-being? Or in the Symposium where he says that the form beauty "without increase" imparts beauty to all beautiful things? According to Bergson, becoming is effectively eliminated by this approach. But it is the reverse that is true, for Plato's categories of light and heavy, fair and foul, etc., are successive positions of the moving reality between them.

"Ancient philosophy," explains Bergson, "expresses the natural tendency of the intellect," which is to resolve the moving into fixed and stationary immobilities. Thus, the "contingent must always be regarded as inferior to the eternal."40

In another reference to Plato, he gives his own definition of "forms" as a framework of presupposed categories into which everything is fitted:

According to Bergson, things are not imperfect and multiple copies of the forms, but the forms are imperfect and multiple copies of the things. Bergson insists that the characteristics of the forms as "separate, simple and everlasting" reveals their true nature as mere concepts framed by our intellect. For concepts are simple and separate from each other, always the same and identical with themselves and isolated from other concepts. And they are static and unchanging; immobile and easier to grasp and take hold of, so that reality can be manipulated in a predictable manner.

Concepts, which Plato believes to be self-subsisting, objective realities called forms, have the very characteristics attributed by Plato himself to the many manifestations of the form which he called their copies. The forms are simple, unique, unchanging within themselves. Now that is just the nature of a copy or picture; it is fixed, unmoving, unmixed with anything else. You cannot even think of two snapshots as interpenetrating each other, or as exhibiting any movement. No wonder Bergson actually calls the forms "snapshots;" a direct contradiction to Plato.43

These snapshots are the reflection of becoming, which essentialists try to make the reflection of the snapshots. They are instantaneous "clicks" of the intellectual mind, which Bergson likens to a camera, calling it "cinematographical."44 It is just their lack of becoming and change, therefore, that makes them what they are. Time does not, in Bergson's words, "bite into them" and cause them to change.45

We see then that Bergson objects to the static, fixed quality of Plato's forms because this quality shows them up as mere concepts or pictures of the true reality, so that becoming must be the true reality instead, of which the forms are the picture. Another of Plato's characterizations of the forms that Bergson disputes is closely related to the previous one: that the unique and self-identical forms represent what is essential among many concrete (or bodily) things which resemble them. In other words, the forms are the essence of the many things in the world of action (Republic 476). They reduce the many into one "independent being." Bergson contends that here lies not only an illusion but "a very serious danger,"46 which lies in their misleading us about the objects we know, giving us only the most impersonal and unessential abstract aspects of them:

Thus, uniting objects under a form leaves only their shell; their shadow, as it were. Here we see the argument with the essentialist mentioned before under our definition, who claims knowledge is the general structure or law that accounts for the particulars. We also hear the contemporary cry of people not to be "reduced to a mere statistic" or "a number."

We saw that Plato represented the changing as eluding the characteristics of fair and foul, hot and cold, light and heavy, etc. We saw also that it was multiform, exhibiting a mixture of many particular things of which the forms are the unmixed essence. It also perishes rather than endures, and is visible rather than invisible. Finally, the changing, and its mode of being, time, is "a moving image of eternity;" that is, reflection, not reality. We shall show Bergson's answers point by point and, in doing so, represent his own picture of "the changing" which he calls "duration."

First, Bergson believes the movement between forms such as fair and foul, or hot and cold, is real, while the forms are its reflection. He contends that to explain change by static forms is to say movement is made of immobilities, which is absurd. We saw before that the forms are defined by Bergson as only the "successive positions" of this movement. He gives us many illustrations of this point throughout his works.

For example, says Bergson, when I move my hand, it is a simple act, but it appears to our mind as the curve A-B containing successive positions, instead of the progress of the movement itself.48 Plato saw as reality the general conceptions, such as hard and soft, fair and foul, between which the object passed. Bergson agrees with Plato that the objects known to the senses or intuition (concrete reality) cannot be resolved into the concepts they exhibit, first one and then another. But for Plato the forms are therefore real, while for Bergson this same fact demonstrates they are shadows.

Another illustration runs as follows: By multiplying photographs of an object in two thousand different aspects you will not reproduce the object itself.49 Nor could many colored mosaics imitate an artist's painting produced in a simple, undivided act.50 So a person who has really seen Paris as a whole can make a series of sketches and attach to them the name "Paris." But the observer of the sketches and the name could not gain an intuition of what Paris is really like.51

According to Bergson, these forms and images arise from our tendency to notice the separation between our states of consciousness, instead of their interpenetration.

Bergson's position, in contrast to Plato, is that all reality is "actions", "flux" or "movement."53 Furthermore, our own consciousness is our best access to this flux, and the "model of which we must represent other realities."54 But the instantaneous cuts (snapshots) the intellect takes, and science uses, make reality out to be a succession of static presents.55 There is then no change and no growth, because there is no time, with its past, present and future. Plato says time is an image; others say it is an illusion of the mind, and that concrete reality is an eternal now (Zen and the Esalen movement, for example). Even Existentialism itself, in upholding the lived and the concrete, is often mistaken for a philosophy of the "here and now." But this is emphatically not Bergson's view. Time is the basic reality of lived, concrete consciousness, because for him life and consciousness occur only in becoming and time. Without time there would be no memory, and thus no continuity of consciousness. The alternative is identical present moments replacing one another, which would result in death or unconsciousness. For Bergson, "whatever lives has a register open somewhere in which time is being inscribed."56 A tree, with its rings, is an obvious example.

As we might think, our awareness of time, which makes us alive for Bergson, requires memory. But Bergson says memory is not the conscious recollection of specific incidents which we store in our brains, as we usually think. It is not primarily the conscious recollection of something. Instead, all of our past is "preserved by itself, automatically." "It follows us at every instant"57 and is involved in everything we do. We may "think with only a small part of our past, but it is with our entire past, including the original bent of our soul, that we desire, will, and act."58 And the fact that the past is always there makes it impossible ever to live it over again.59 Therefore, because what lives has a history, it experiences each moment as new; in fact, as unpredictable. Memory then implies (paradoxically) novelty, because the next moment must be different from the one before, if only because the first moment is now remembered.60

This means our consciousness is always entering the present, which is always new.61 Nothing ever remains the same, because life is constantly joined to its entire past, so that repetition is impossible.62 The intellect, however, seeks to represent the moving by rearranging what is already known, according to its principles "like is like" and "all is given."63 Change is then explained as simply the rearrangement of the unchanging fragments extracted by the mind, and everything which changes is identified as the expression of something static which can be known in advance. But as we saw, our consciousness is fluid, not a series of successive instants, presents, or solids, which remain the same within themselves or which can be foretold in any way.

The temporal, the alive, the real, the changing, and the new are thus bound together in Bergson's characterization of duration, or the changing. Time, therefore, is not the moving image of eternity. Eternity, as the Forms, is the static image of time. In a sense, eternity for Bergson exists as the continual and unceasing creative activity as the changing itself.

Plato also said that the changing is multiform, exhibiting a mixture of many particular things of which the Forms are the unmixed essence. Bergson says the grouping of examples under a form is forcing them into a pre-existing frame already at our disposal. And it is this pre-existing frame, composed of concepts, which make the world appear to be a multiform group of examples. Concepts, not things themselves, make the world appear as "many things." It is not the eye alone, as Plato thought, that causes this false appearance, but the intellect assisted by the eye.64 It is the general concepts, singular and external to one another, which create the idea of "things" such as a bed or just acts. The many things are produced by the categories which divide up the world. Of course, Plato could point out that there are many more things than categories; many beds, but just one form of bed. But this is to be expected since, because reality is really fluid anyway, all things grouped under "bed" are likely to appear different.

Plato also saw the changing as "becoming and perishing." But while Bergson would agree that it becomes, he basically disagrees that it perishes. As we saw, in real time (duration) the past is preserved forever. Therefore it continually accumulates:

Furthermore, only that which changes endures:

We see again that, for Bergson, permanance and "eternity" are in the changing. By contrast, the unchanging psychic states, from which the forms arise, are not permanent. It would seem, then, as a moral consequence, that if Bergson is right, we do not develop the eternal and divine in us by concentrating on the Ideas, as Plato suggests. We do so by concentrating on the changing. However, Bergson says this does involve a sort of "reason," as we will discuss toward the end of the epistemological section of the comparison of Plato and Bergson.

In summary, we have seen that Bergson describes duration in terms of flux of consciousness, which only appears as a series of states; and as time, which assures novelty. Bergson agrees with Plato that the flux eludes the forms which it exhibits, but differs in saying flux is real. He also differs in saying this flux only appears multiform when we see it in terms of forms, which are our own concepts. And the eye is the servant of reason, so that the forms are in the realm of the visible, contrary to what Plato said, because reason and sensation together isolate visible, separate objects.67 And finally, eternity is in the changing.

E. Summary of the Debate on Metaphysics

Let us summarize the opposition between essence and existence exhibited in the opposition between Plato and Bergson on form and becoming. Plato believed that the forms were real, because they are the unchanging essences by which everything else is described and known. What is meant by beauty or justice if it is simply many beautiful objects or just acts? These do not exhibit the full nature of the form, for they are always liable to change into their opposite. Bergson, on the other hand, said these forms are only "snapshots" of the changing reality taken by the intellect, born of separate acts of attention. Beauty cannot be resolved into one of these snapshots; it consists in the pure, undivided act which is creating something new that the intellect, with its static, immutable forms could not have conceived.

A play on words illustrates the argument. Bergson thought forms were only instants isolated from the flow of becoming. Plato thought the many sights and sounds were only instances of the eternal, single and unique forms.

PART TWO: EPISTEMOLOGICAL

The second question in this debate between Plato and Bergson on essence versus existence is the epistemologicalo question. Is reason the best way of approaching reality, or is the best way through a faculty which Plato calls "opinion" and Bergson calls "intuition?"

A. Plato on Reason and Opinion

Plato defines reason as the faculty which knows the forms. Since the forms are real existence, it follows that reason is the way to reality. In Republic, Book Five, "knowledge" is defined as the faculty that knows things in themselves, or the forms-- such as beauty and justice. On the other hand "opinion" is defined as the faculty which acquaints us with many beautiful things and just acts without discerning their essence. It is defined in Book Five (478) as the faculty between intermediate knowledge and ignorance.68 The objects of "opinion" can both be and not be, since they wander between the forms, and are therefore placed "in the interspace between being and non-being" (Republic 479C), or as Bergson said, considered a "mere diminution" of the forms.39 In Plato's view, intelligence or "intellection" knows the real, while opinion knows the changing.69 Thus, since Plato believes forms are prior to the changing, reason which knows the forms is prior to the faculty which knows the changing (becoming), which must therefore be called mere "opinion."

B. Bergson on Intuition and Reason

Bergson, naturally, takes the opposite stand. Since the changing is prior to forms, the faculty that knows the changing must be prior to reason, the faculty that knows the forms. And it cannot be called opinion, but must be entitled "intuition."

Harod Larabee speaks of Bergson as "one of the pioneer figures of the revolt against reason."70 The following remark in Creative Evolution makes this very apparent:

On other words, reason falsely believes it knows the absolute, because it has taken hold of reality as though it is likely to remain always the same. It deals "with the old which can be repeated"72 and resolves the real into static categories known in advance:

What does Bergson put in place of reason? Something roughly equal to Plato's opinion. Bergson calls it "intuition." Many philosophers, such as Kant, define intuition as the direct perception of an object, usually through the senses.74 This is exactly what Plato meant by opinion. It is very close to what Bergson means by intuition, too. But Bergson puts a bit more into his view of intuition than Plato puts into his view of opinion. Of course, as we will see, we could also say that Plato put more into the concept of reason than Bergson did.

Bergson defines intuition as "following reality in all its sinuosities and of adopting the very movement of the inward life of things."75 In other words, it is the most direct and intensive perception of a changing object. It is the "intellectual sympathy by which one places oneself within an object in order to coincide with what is unique in it and consequently inexpressible."76 "Philosophy," says Bergson, "consists precisely in this, that by an effort of intuition one places oneself within concrete reality . . ."77

The real, the absolute, is the concrete reality that we know directly. Does this make Bergson an empiricist? In a sense, yes; he believes that we must look to the facts of experience.78 But Heidegger has pointed out, in developing his own notion of contact with concrete reality, that direct experience is not always "immediate" because reality (or as he calls it, being) is not easy to know. It is subtle, elusive; and thus requires careful attention.79 So this is a very sensitive type of empiricism. It is "sympathetic" as Bergson says. It aims to "tune in" on reality as we experience it, almost like a telepathic communication; not merely noting the existence of this or that concrete fact (the less-sensitive empirical approach which closely resembles Bergson's incorrigible intellect that identifies everything as "this or that" and always asks what category already in mind it is to fit things observed; which is, in fact, the way "empirical" scientific method usually works, as I see it).

The main thing Bergson adds to Plato's opinion is self-introspection. For Bergson, the more deeply we go into our inner selves, the more truth and reality we discover.80 We saw that essentialists tend to shy away from introspection as too subjective. Although Plato certainly does not shy away from the soul, he discusses its "parts" and reveals its structure,81 rather than directing the reader to tune in on its concrete existential flow. We must emphasize that this self-reflection is the essence of Bergson's intuition (as knowledge is, for most existentialists). It is not primarily sense perception. That is why I have referred to "concrete existence" rather than to "the visible" as Plato usually does. This is precisely because existentialists view the concrete as spiritual, not merely physical and known through the senses alone. For Bergson, intuition could result from observation through the senses, for we see the flow of reality there, too. But the most intimate contact is found through observation of the soul. Reason even plays a part in this intuitive process. It plays a subordinate and illustrative role as the construction of fluid images and the use of science to foster the intuitive vision.82

C. Can Plato's Reason Also Be Entitled "Intuition"?

But this raises a question. Does Plato have a conception of intuition? Is it part of his conception of reason, which would confirm that it is more than a process designed to master matter, and thus merely conceptual and logical, putting together static parts external to each other, as Bergson claims? There are hints that this is so. In the Myth of the Cave, at for example 518E, he repeatedly speaks of the faculty of reason as "seeing" and also speaks of the eye of the whole soul.83 This seems to be a higher kind of vision of a direct and intuitive kind. But this "eye" may be just a metaphor, and we must remember he also speaks of reason as "a strict process of thought,"84 and as "calculation" (Book Ten).85 What "seeing" could mean, is that the forms themselves are not known in the conclusion of an argument, as indeed he states in Book Six (that they are not).86 Instead we apprehend them without knowing exactly how. We go beyond the "mere reasoning process" to use hypotheses as "stepping stones whereby it may force its way up to something that is not hypothetical, and arrive at the first principle of every thing, and seize it in its grasp" (Davies/Vaughn translation)87 (or "rising to that which requires no assumption and is the starting-point of all, and after attaining to that again taking hold of the first dependencies from it"-- Shorey). We may not realize exactly what dialectical, logical processes led us to this realization. We could say that this is a more sensitive rationalism, just as we said Bergson's was a more sensitive empiricism. At one point, as suggested above, Bergson seems to describe intuition in much the same say: as a sudden, unreasoned vision of the wholoe that follows the study of many separate facts or ideas.88 But unlike Plato, Bergson does not reach first principloes or eternal laws, which he conceives as mere concepts abstracted from reality. Bergson's intuition is not of principles; it is contact with reality as flux.

It may be that by "seeing" Plato means to actually "see" the essence of the form. But this seems meaningless in the usual sense of "see." To see something, whether it be physical or not, there must be some kind of image seen; a particular perception of, for example, Socrates, or a beautiful object. Otherwise perceiving a form is nothing more than perceiving any concept or logical idea. But Plato said forms are beyond both images and concepts.89

D. Different Visions of the One

There is one way in which Plato and Bergson could be mistaken for being in agreement, a way in which they are in fact not. Both seem to prefer the one to the many, uniting many particulars in a vision of what is real in them. Both speak of penetrating to the essence of things. Could the realization by Bergson that many states are part of one Becoming be the same as Plato's realization that the many similar objects manifest one and the same form? No, because for Plato the essence is an unchanging universal form, different among other forms, which transcend concrete, visible reality. For Bergson, on the other hand, the "essence" is an unobstructed view of the object itself as it is before you, whence you see it is not a thing in space or a concept, but a part of moving reality.90 Unlike Plato, Bergson does not want to go beyond the object, and all the general laws or ideas he may come up with are so many paths to an intuitive vision into which they have melted. His goal is not a general structure, but intimate contact with existing, observable reality itself.

In any case, Bergson would want to "reconcile" in becoming a pair of opposites like fair and foul, or light and heavy.91 Plato would want to see the essence of a series of fair objects, or light objects only. Plato unifies many moving, concrete objects into one unchanging form or concept. Bergson unifies many static concepts or forms into one changing, concrete becoming.

E. The Absolute

There is one point on which they do agree, however. Both do believe in an absolute. Naturally, Plato and Bersgon conceive the absolute in opposite ways and in opposite realms. For Plato it is forms; for Bergson concrete becoming. We saw that Plato thought forms such as beauty were absolute. Bergsons's view of the absolute is direct contact with the changing objects.

Reason is relative because it depends on the translations and symbols of the observed object, rather than the object itself. But:

To the extent, therefore, that Plato's reason and Bergson's intuition are characterized by knowledge of the absolute, they both have something in common.

F. Comparing Plato and Bergson on Intuition, Reason and Opinion

Let us assume that there is a sort of intuition involved in Plato's reason. We can then size up the comparison between Plato and Bergson epistemologically this way: Plato appears to see "intuition," the knowledge of the real immediately given, in the contemplation or seeing of the true and eternal essences. Bergson sees intuition, and applies this precise term, to the contemplation of the changing. Bergson see true, intuitive grasp of the real operating in what Plato would call merely the "realm of opinion." Plato sees "intuitive seeing" as operating in the realm of what Bergson would call mere "static concepts abstracted from the real." Both see a realm of reality which casts shadows; for each the opposite realm is considered real, which is therefore the one in which their "intuition" operates.

PART THREE: COSMOLOGICAL

A. The Priority of Soul over Matter

It is incontestable that both philosophers believe thay have shown that soul is prior to matter. We mentioned before that all essentialists and existentialists make the same contention, though they may describe it in different ways.

Plato makes his view crystal clear in the Laws. There he states that the self-generating motions of the soul, such as wish, reflection, and love, explain motion caused externally, such as generation and destruction.94 He proves it to my satisfaction in this quote:

This self-generating motion is equivalent in many ways to Bergson's "original vital impetus" which is also prior to matter. As he explains it in Creative Evolution, this original impetus is prior to matter much as a jet of steam which is "nearly all condensed into little drops which fall back, and this condensation and this fall represent simply the loss of something, an interruption, a deficit."97 God or the soul is "a reality which is making itself," while matter is simply the motion resulting when it begins to fall back and "unmake itself."98 The whole purpose of Creative Evolution is to show that "the vital is in the direction of the voluntary,"99 and that life and matter are the results of an originating impetus instead of external mechanical causes. This is exactly what Plato maintains in the Laws. But Bergson had another purpose in mind, too: to show that life and matter are also not results of a realm of forms given in advance. Which brings us to the question of the two (or actually three) kinds of "order."

One of the implications of the soul's priority over matter for both philosophers is the notion of two difference kinds of order. For Plato, mechanical necessity is opposed to purpose or design which seeks to "persuade" it.100 The first kind of "order," as Bergson calls it, is much the same in his own view, but he claims his second and higher kind, corresponding to Plato's order of purpose and design, is something more. He classifies the Platonic type of higher order as "finality" which has the defect of all intellectual conceptions, in that it seeks to arrange everything into already known categories. Order as the realization of a purpose or carrying out of a plan requires that the future be already given and known. While Bergson's higher order "has something of finality about it," he prefers to define it as something like a work of art or a creative action. For example, a Beethoven symphony is highly ordered, but its production, and its course as we listen, is original and unpredictable.101 I might add, too, it is a constant flow, whereas the forms toward which the soul persuades necessity are not. Essentialists might point out that some creativity, at least, is more like the imitation of the eternal, already-existing forms rather than the creation of new, more-fluid ones. I suspect this may be true at least of classical rather than romantic types of art. Classical art is indeed based on the essentialist point of view or attitude that the principles of true beauty and order have already been given. These two versions of higher order are in fact the results of the two competing ideas of what spirit is, essence and existence, which we will now compare.

C. Recognizing the Two Views of Spirit

It is clear that both philosophers believe in a spiritual order higher than necessary causation. But they disagree about what that higher order is, because they disagree about what is fundamentally real and spiritual. What each is forced to do by his ideas is to identify the soul with his own metaphysical reality and link matter with the corresponding shadowy reality. Each argues, therefore, that matter belongs in the realm the other considers to be real. So Plato identifies spirit with the forms and matter with becoming, while Bergson identifies spirit with becoming and matter with the forms. What is more, they do so without disagreeing substantially on the nature of matter and spirit, just as they substantially agree on the nature of form and becoming!

Plato links the spiritual life with knowledge of forms, while Bergson declares that knowledge of forms is part of the same reversal or interruption of the spirit as matter itself is. Conversely, Plato practically identifies "what becomes and perishes" with matter, while for Bergson becoming and duration are found most clearly in the soul.

If we are able to show that Plato and Bergson argue successfully their opposite views of the place of spirit and matter, and still agree that spirit is primary, it will be clear that the argument over essence and existence cannot be confused with the more obvious and familiar one of spirit versus materialism. It is not necessarily the case, although it is customary to think so, that it is the same argument. Nevertheless, both Plato and Bergson, and the two schools in general, believe it is the same argument and that their opponents are materialists without knowing it; that is, that their professed belief in the soul is inconsistent with their other views. But if both Plato and Bergson escape the charge of materialism, as I believe, then we know the dilemna is greater than either believes, for two views of spirit must be reconciled.

We shall begin with the manner in which Plato's soul links up with the Ideas. We will find this somewhat-complex discussion also sheds light on such important aspects of the debate as whether Plato derives all motion from the unmoving, as Bergson claims, and whether his reason is really different from necessity.

We said that Plato believes the spiritual life involves transcending the pollutions of the material. He stated this several times in the Republic, most notably in the Myth of the Cave (Republic 519B) where the soul must be led away from physical pleasures, which he calls "leaden, earth-born weights," in order to become enlightened, which means to know the forms.102 We also know that Plato defines the soul as self-generating motion. By this he also means life.103 Here he is very close to Bergson in asserting that life is an originating principle rather than a result of necessary causes.

This Platonic soul has a higher and lower side. The higher, good side is rational and exercizes self-movement according to reason, bringing order to physical motions, while the lower side is irrational and swayed by these motions, so as to bring chaos.104 The forms are the model the soul looks to in ordering the universe and persuading necessity.105 The type of self-movement that is rational is itself said to be closely akin to the forms. That movement in the Timaeus is called the "circle of the same," motion on one's own axis to use a planetary analogy, which is, like the forms, regular, uniform and unchanging in its relation to other objects.106 So far the rational part of the soul is closely akin to the forms, its model, and true spirituality is to get to know them; but the soul itself cannot yet be identified with forms. If it were, it would be hard to account for movement, either of the soul or anything else, and Bergson would be right that Plato's system allows for no motion or change.

In Francis MacDonald Cornford's view, expressed in his Plato's Cosmology, the soul, or demiurge, is an independent element.107 But I suspect Plato actually characterizes everything as forms and diminution of forms. This may weaken Plato's case, but not destroy it; it means he fits even better into the comparison of two spiritual philosophies sharing a fundamental disagreement. The soul then would be a form itself, or at least much closer to forms than to becoming and bodies. This is in fact what he implies in the Phaedo, where the soul is proved immortal because formal essences like beauty are.108

There is strong evidence that the soul is a form in the Timaeus. There the World Soul is described as being composed of three forms: sameness, existence, and difference. The latter gives the soul an affinity with changing things, although not itself changing.109 The point is clear: the world soul is composed of forms. This applies also to the Gods and to the divine or rational part of human souls.110